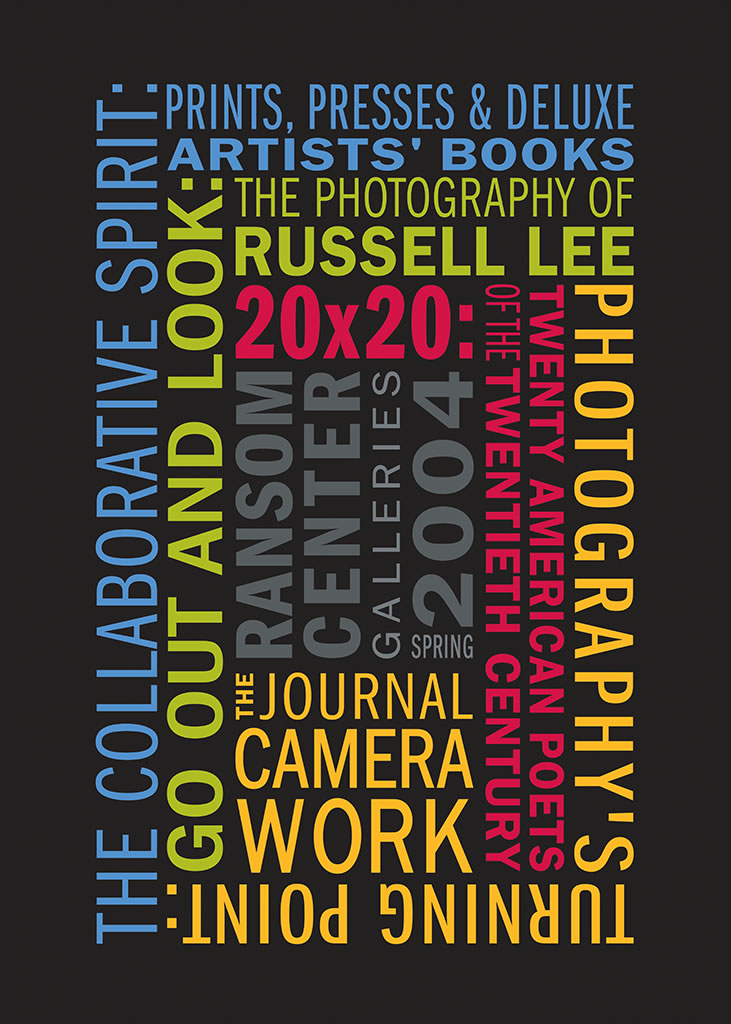

Photography's Turning Point

The Journal Camera Work

April 20, 2004 – October 17, 2004

The University of Texas at Austin's Harry Ransom Center hosts the exhibition "Photography's Turning Point: The Journal Camera Work" from April 20 through Oct. 17, in the Ransom Center Galleries. The exhibition of 37 prints is drawn solely from the Ransom Center's collections, which contain one complete run of the bound journal Camera Work, duplicate copies of several issues, plus hundreds of unbound photogravures.

"Only examples of such work as gives evidence of individuality and artistic worth, regardless of school, or contains some exceptional feature of technical merit, or such as exemplifies some treatment worthy of consideration, will find recognition in these pages." With these words in 1903, Alfred Stieglitz introduced the quarterly journal Camera Work, one of the most influential and important publications in the history of photography.

Using images from Camera Work, the exhibition examines the development of modern photography by demonstrating photography's dramatic shift from early Pictorialism to Modernist photography, including the work of photographers who would become some of the most famous in the medium's history -- from Gertrude Käsebier, Clarence White, Edward Steichen, to Paul Strand and Stieglitz himself.

It was in the early 1900s that photography went stylistically from being soft in focus and concerned with domestic, feminine and nature themes to being sharper in focus, with greater formal experimentation and with more urban themes. Portions of the exhibition demonstrate this trend while other sections show the modern art and historic photographs these modern photographers were looking at and by which they were influenced.

During its run from 1903-1917, Camera Work presented advanced work from American and European photographers. The journal was a high-end production -- quality that was to mirror the importance of the images it contained. It was made up of exquisite photogravures hand-pulled from the original negatives onto Japanese tissue and tipped into each copy by hand.

The journal not only illustrated contemporary photography, it also reproduced works of vanguard modern art, publishing Rodin's and Matisse's drawings three years before the landmark Armory show exhibition in 1913.

"What makes Camera Work such a landmark publication is that it promoted and presented a dramatic shift in artistic photography -- from Pictorialism to Modernism," said David Coleman, the Ransom Center's associate curator of photography and curator of the exhibition. "We can see the first seeds of modernist photography, nascent in some of its early images, mature into the powerful images of Paul Strand."

George Eastman's introduction of the Kodak camera in 1888 made it possible for the average person to take pictures of everyday events by simply pressing a button. Snapshots consisted of unpretentious images of families at leisure, at play and on vacation.

Yet there were many photographers who reacted against this snapshot sensibility, specifically the Pictorialists. A diverse group of creative photographers throughout Europe and the United States, the Pictorialists were serious about creating images that could be considered to be works of art. Instead of taking photographs for documentary purposes, the Pictorialists used the camera to express emotion and individuality. Rather than capture facts in their photographs, they were concerned with creating beautiful images.

"The exhibition presents a turning point in artistic photography's style," said Coleman. "By the journal's last issue, photography as a creative medium had changed forever. Viewers will be able to trace this evolution through the displayed images in the exhibition as well as understand photography's ability to present not only hard facts, but also emotion and expressive individuality."