International Human Rights

Writers and Free Speech

Writers in Exile / Global

Refugees

Writing the Cold War

Writing World War II

Digital Collections

International Human Rights

PEN was founded in 1921, predating the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United

Nations in 1948. PEN did not always consider itself an international human rights organization. The fact that

it became one of the oldest of such organizations was due to a complex set of circumstances and changing

international pressures that pushed PEN to act on its writers' behalf. This is not to claim that PEN was a

reluctant human rights organization. Instead, it is to acknowledge the many ways PEN sought to alter its

mission, and its goals to maintain the commitment to the organization's founding values. The materials in this

guide highlight PEN's responses to these pressures, and its interventions in response to a number of human

rights issues, from gender-based discrimination, to the suppression of free speech, to the incarceration of

dissident writers and activists. By engaging with these materials, students will have the opportunity to

track, across many different circumstances, PEN's evolving understanding of itself and of international human

rights as a political concept.

Fundamental Values: PEN and Human Rights

While PEN was founded as a social club for English writers, its rapid growth on an international scale soon

forced the organization to reckon with the political differences between its increasingly diverse member

centres. While John Galsworthy (first President of PEN International and 1932 Nobel laureate in literature)

could state in 1932 that PEN "has nothing whatever to do with State or Party politics," the rising crisis of

World War II demonstrated the need for the organization to define its political allegiances and principles.

These materials offer snapshots of PEN's developing stance towards writers' social and political

responsibilities before, during, and after World War II. Students might use these documents not only to

understand the history of PEN, but also to consider what political responsibilities are shared by writers,

artists, and other public figures, and how these responsibilities are identified or adopted. How does

Galsworthy's claim that "PEN stands for humane conduct," for example, transform into an international focus on

what we now refer to as "human rights"?

View Item

"What the P.E.N. Is." Opening Remarks by John Galsworthy written for the 10th International PEN

Congress, Budapest, Hungary. 1932.

PEN Records 81.3

View Item

"Appeal to the Conscience of the World," letter from PEN London Centre. June 1940.

PEN Records 91.5

View Item

"Fundamental Values," letter to PEN members from PEN London Centre. 1943.

PEN Records 110.3

View Item

"Suggestions for the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Assumptions and Values," proposed program for a PEN

symposium. 1943.

PEN Records 110.3

PEN and Politics

As PEN's principles evolved, the organization's commitment to free expression as a fundamental human right

came to play a central role in its political negotiations, both internally and in the public eye. Tensions

arose between PEN's founding centres in the U.K., America, and Western Europe and centres in countries whose

political regimes were often hostile to the ideals being written into the PEN Charter. While PEN's

international leadership sought to avoid political conflicts or partisanship, it often had to reckon with

contradictions between the organization's core values and the concerns of writers with complex political

allegiances. The materials below help illustrate tensions in PEN, both internally (between centres in Soviet

countries and those in the West during the Cold War), and externally (between members of "official" PEN

centres endorsed by authoritarian regimes and other writers being repressed by these regimes). Students

approaching these materials might consider how they illustrate the conflicting values and interests at work in

any international organization, and what happens when a commitment to human rights runs up against other

organizational priorities, like promoting dialog between opposing nations who disagree on what those rights

entail.

View Item

Letter from Agrupación de Intelectuales, Artista, Periodistas y Escritores (A.

I. A. P. E.) to delegates of the 14th International PEN Congress in Buenos Aires, Argentina, with

Spanish and French translations. September 1936.

PEN Records 83.2

View Item

Proceedings and Resolution regarding the PEN Hebrew Centre from the 20th

International PEN Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark. June 3, 1948.

PEN Records 87.5

View Item

Letter from Hanoch Bartov, President of PEN Israel, to the Editor of Al-Fajr [English

Edition]. January 2, 1993.

PEN Records 209.3

View Item

Letter from Friedrich Bruegel, chairman of PEN Centre for Writers in Exile, to David Carver. April

20, 1954.

PEN Records 155.4

View Item

"P.E.N. In The Soviet Union," confidential memorandum of a conversation between Alexandre Blokh and

Josephine Pullein-Thompson. April 1987.

PEN Records 257.7

Religious Freedom and Tolerance

These materials illustrate PEN's reckoning with the tension between religious freedom and freedom of speech

in the Salman Rushdie crisis of 1989. While PEN centres around the globe denounced the fatwa against Rushdie,

debates soon arose in the United Kingdom regarding what happens when a writer's words violate core tenets of a

particular religious system. As Muslim groups in the U.K. called for Rushdie's works to be banned under a

longstanding anti-blasphemy law, British clerics, politicians, and intellectuals all weighed in on where to

set the boundaries between the fundamental human rights of free expression and religious tolerance. Students

working with these materials might consider what happens when human rights seem to conflict: who interprets

these rights? Who decides what is protected, and what is not? What power dynamics are involved in the decision

to defend some liberties at the expense of others?

View Item

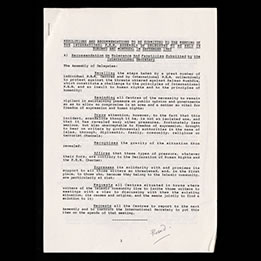

"Recommendation on Tolerance and Fanaticism Submitted by the International

Secretary," memo for International PEN Assembly of Delegates in Toronto and Montreal. September 1989.

PEN Records 223.1

View Item

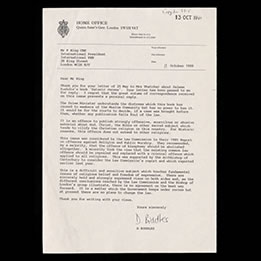

Letter from the U.K. Home Office to Francis King regarding U.K. anti-blasphemy laws. October 11,

1989.

PEN Records 262.4

View Item

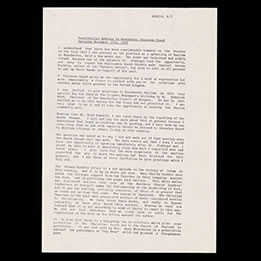

Presidential Address from the Bishop of Manchester to Diosecan Synod regarding Rushdie death threats.

November 25, 1989.

PEN Records 262.4

View Item

Correspondence between Josephine Pullein-Thompson and Michael Knowles, M. P.

regarding Salman Rushdie case. February 28—March 21, 1989.

PEN Records 262.3

Protest and Incarceration

These materials mark points of conflict between writers (and organizations like PEN) and governments over the

definition, application, and protection of human rights. In the latter half of the twentieth century, PEN

repeatedly advocated for writers facing imprisonment, deportation, and even death, at the hands of the

political regimes they opposed. From Chinese writers and scholars imprisoned after the Tiananmen Square

protests to an American poet and activist at risk of deportation for her support of socialist ideas, these

writers' right to free speech was often limited as a result of their advocacy for other human rights being

denied by the governments they criticized. These materials offer students an opportunity to consider the

fraught relationship between state power and human rights. How does free speech relate to other rights like

free movement, equal representation, or economic and environmental justice? How have governments and

corporations justified the curtailment of these rights?

View Item

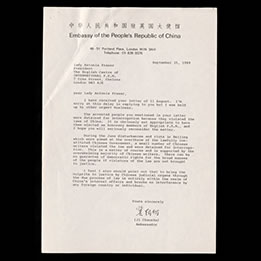

Letter from Chinese Ambassador Ji Chaozhu to Antonia Fraser. September 15, 1989.

PEN Records 242.5

View Item

Correspondence regarding the deportation of Margaret Randall between the PEN

American Center, Josephine Pullein-Thompson, and George Shultz, U.S. Secretary of State. January 16,

1986 and February 26th, 1986.

PEN Records 257.7

View Item

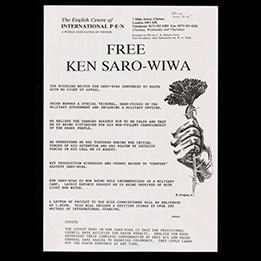

"Free Ken Saro-Wiwa," protest information sheet from PEN Writers in Prison Committee. November 9,

1995.

PEN Records 246.4

View Item

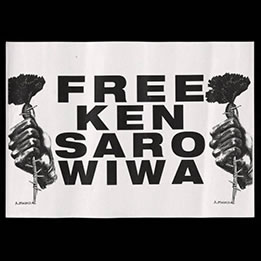

Protest sign for PEN Writers in Prison Committee event in support of Ken Saro-Wiwa. Circa 1995.

PEN Records 361.3

View Item

Letter from Shell International to PEN International Chair Joanne Leedom-Ackerman regarding Ken

Saro-Wiwa. December 21, 1994.

PEN Records 246.3

View Item

"Report on Five Croatian Women Writers Currently Under Attack," report to International PEN Women

Writers' Committee. February 20, 1993.

PEN Records 209.3

Writing on the Silences: What Is Missing?

PEN would have to grapple with a complex set of binaries as it positioned itself as a human rights

organization. Some of these include: local versus global, home versus exile, free speech versus dissent. It

would also have to contend with conflicts and disagreements that were bound up in other more intractable

disputes such as religious conflicts and the legacies of colonialism embedded in racial and gender politics of

the time. We can search through the collection and find fierce advocacy for some writers, but no evidence of

protection for others.

View Item

"Resolution on South Africa Submitted by the U.S.A. West Centre," for

International PEN Assembly of Delegates in Toronto and Montreal. September 1989.

PEN Records 223.1

View Item

Opening Statement by Lily Tobias for a meeting of the South African PEN Club

at the Carleton Hotel in Johannesburg, South Africa. February 28, 1945.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

Two poems by Jacques Roumain, "Guinea" and "When the Tom Tom Beats," and a typescript account about

the author. 1935.

PEN Records 77.2

Women's Rights and Expression

PEN expanded the definition of its political and ethical responsibilities in the decades following the Second

World War, which saw the creation of a number of new committees aimed at addressing specific international

issues. The PEN International Women Writers' Committee was developed in response to a sense that the

challenges facing writers around the globe often had a greater urgency for women—particularly those working in

countries and cultures with a history of patriarchy and gender-based discrimination. While the formation of

the Committee was met with some controversy (see the "Writers and Free

Speech" teaching guide for materials that document this), it led to a number of efforts on the behalf of

women writers being silenced by their own governments. PEN was largely founded by women, and developed many of

its humanitarian programs under the guidance of women officers, including Storm Jameson, Janet Chance,

Josephine Pullein-Thompson, and many others. These materials offer a glimpse at contemporary efforts by PEN

and other advocacy groups to address ongoing issues of gender discrimination and human rights violations

against women. Students might use these materials to explore how discussions of human rights have

coincided—and clashed—with those of women's rights and gender equality. How have women been excluded from

accessing the rights and privileges extended to men? How do women writers respond to this? What strategies are

available to feminist writers and thinkers to combat patriarchy?

View Item

"Women and 'Cyberdissent': Tunisia, Iran and China," PEN Writers in Prison Committee program for

Women's Day. March 8, 2005.

PEN Records 248.1

View Item

Letter from Meredith Tax to Members of the International PEN Women Writers' Committee. September 18,

1994.

PEN Records 242.3

View Item

"Draft Program for the 4th World Conference of Women and NGO Forum, Beijing, 1995: Culture and Human

Rights." 1995.

PEN Records 242.3

View Item

Letter from Leah Fritz to Josephine Pullein-Thompson regarding Afghan women writers in response to

Rushdie case. February 19, 1989.

PEN Records 262.4

Dissidents within PEN: Enforcing the Charter

Part of PEN's development into an international human rights organization was the creation and evolution of

the PEN Charter, a

document each new member signs upon joining the club. The first official PEN Charter was ratified in 1948, as

the organization began to reckon with the aftermath of World War II and the beginnings of the Cold War. Aside

from a 2017 amendment extending the "hatreds" which all PEN members must oppose from those of "race, class,

and nation" to "all hatreds," the Charter has been a touchstone for the institutional values shaped during

World War II. The materials below document the ratification of the Charter and offer examples from PEN's

history in which it had to be invoked against members who violated its principles. Students might consider the

historical context of the first Charter's ratification, or the political tensions that produced the need to

state principles that had previously been merely implicit to the organization. How does the Charter speak to

the vast range of cultural difference represented in PEN's global centres? How can documents like this, or the

United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, cut across international boundaries? What do these

documents enable, and what are their shortcomings?

View Item

"P.E.N. Charter," from the 20th International PEN Congress, Copenhagen, Denmark. 1948.

PEN Records 87.5

View Item

Proceedings regarding the ratification of the PEN Charter from the 20th International PEN Congress,

Copenhagen, Denmark. June 3, 1948.

PEN Records 87.5

View Item

Correspondence and press clipping related to Gerry Adams's membership in Irish PEN. January 1991.

PEN Records 209.2

View Item

Letter from György Konrád, PEN International President, to Timur Pulatov, President of the Central

Asian Republics P.E.N. Centre. January 26, 1993.

PEN Records 209.4

War and Conflict

PEN's modern identity was forged in the conflict of World War II, and the organization would continue to

intercede in the many armed conflicts that took place in the years that followed. As PEN ratified its Charter

and began to define its role as a human rights organization, advocating for international peace and dialogue

among nations became a central part of PEN's mission. This emphasis on peace emerged from the tension between

PEN's initial desire to remain out of politics—seen in the organization's refusal to take sides in disputes

like the Israeli/Palestinian conflict—and its commitment to combating the suppression of human rights like

free speech and political self-determination. The materials below offer a glimpse at a number of late

twentieth-century conflicts as they were experienced by PEN and its members. If PEN was not always mightier

than the sword, the organization nevertheless worked tirelessly to communicate with heads of state, spread

word of attacks and human rights violations, and encourage cultural exchange between warring nations in the

pursuit of peace. These items provide students a window into the experience of modern conflict, and invite

discussion of the role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) in offering nonviolent responses to violent

situations.

View Item

Letter from Boris A. Novak, President of the Slovene P.E.N. Centre, to PEN International. July 2,

1991.

PEN Records 209.2

View Item

Letter from Miloš Mikeln, Chairman of PEN Writers for Peace Committee, to PEN International. June 28,

1991.

PEN Records 209.2

View Item

Letter from Anatoly Rybakov, President of Russian PEN, to PEN International. July 24, 1991.

PEN Records 209.5

View Item

Telegram from English PEN Centre to Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin. July 25, 1991.

PEN Records 209.5

View Item

Letter from Anton Fredrik Andresen, President of Norwegian PEN Centre, to President Boris Yeltsin.

July 25, 1991.

PEN Records 209.5

View Item

Letter from Nghiêm Xuân Thiện to David Carver and "South Vietnam Bloody New Year," a newsletter by

Nghiêm Xuân Thiện. March 16, 1968.

PEN Records 154.4

PEN and NGOs

As PEN evolved, it developed relationships with other international organizations and writers' groups. Its

advocacy for writers, human rights, and freedom of expression led to natural partnerships with groups like

Article 19, the United Nations, and UNESCO. These relationships offered PEN both financial support and further

avenues for influencing governments on behalf of writers around the globe. The materials below highlight some

of these partnerships, offering students a chance to observe what roles PEN played in these larger

organizations, as well as the limitations faced by a writers' group without governmental affiliation or large

amounts of funding. These materials might prompt discussions of the extent to which NGOs are (and are not)

able to influence governments and policies to support human rights around the globe.

View Item

Memorandum of agreement between PEN and UNESCO. May 19, 1950.

PEN Records 100.6

View Item

Letter of invitation to PEN/UNESCO Conference: The Writer and the Idea of Freedom. 1950.

PEN Records 100.6

View Item

"Part IV: International PEN" in Report to International PEN on the United

Nations Commission on Human Rights, 46th Session, Geneva, 29 January to 9 March 1990. March 30, 1990.

PEN Records 242.5

View Item

"Observations Made in Geneva," by PEN Writers in Prison Committee. February 1990.

PEN Records 242.5

We have attempted to minimize harm or adverse impact by selecting primary sources

that we believe will not place people at risk. Please notify us at reference@hrc.utexas.edu if you believe we need to remove any

materials from this digital collection.

Takedown Notice: This material is made available for education and research

purposes. The Harry Ransom Center does not own the rights for these items; it cannot grant or deny permission

to use this material. Copyright law protects unpublished as well as published materials. Rights holders for

these materials may be listed in the WATCH

file. It is your responsibility to determine the rights status and secure whatever permission may be

needed for the use of any item. Due to the nature of archival collections, rights information may be

incomplete or out of date. We welcome updates or corrections. Upon request, we'll remove material from public

view while we address a rights issue.