Hall-Troubridge Teaching Guides

These guides have been developed to provide resources to instructors interested in teaching with the Hall-Troubridge Digital Collection and to offer students the opportunity to engage with archival resources to enrich their learning experience.

A Biography on Pink Paper

For almost a century, Radclyffe Hall has been both a beloved and polarizing figure for queer people. Synonymous with her book The Well of Loneliness, a watershed text in lesbian literature that was one of the earliest to portray a queer relationship in a sympathetic light, Hall remains an icon among queer authors. The text likewise serves as a source of inspiration to many young queer people who find kinship and familiarty in the story of Stephen Gordon as she came to terms with her outsider status as a queer person in turn-of-the-century Great Britian, many of whom described the book as a "survival guide." However, many queer people have taken issue with Hall due to her Fascist sympathies. The book, advocating for tolerance and acceptance for queer people (whom Hall describes as "inverts"), found itself at the center of a media frenzy, being labled as "obscene" and "immoral" by conservative cultural commentators who bristled at changing cultural attitudes regarding gender and sexuality. In terms of queer media representation, such a fight was not new, nor would Hall's obscenity trial end regulation of queer texts. However, the politics of banned literature can sometimes have a neutralizing effect on authorship, erasing the person behind the book and conflating them with the political conditions of their time. Certainly authors are complicated and imperfect people, with Hall being no exception.

Her partner, Una Troubridge, had her own life and narrative. Buried with the words "Friend of Radclyffe Hall" on her casket, Troubridge's life and contributions are worthy of remembrance and study. While Hall's legacy (over which Troubridge was deeply protective) dominates much of what people know about Troubridge, she too was her own person with depth, interests, and intellect. Like Hall, Troubridge was an imperfect person. Both held reactionary political beliefs typical of their class in regards to race, classism, and even gender expectations. Both went even further by expressing support for Fascism in the 1930s, supporting the political suppression of anti-fascist people and literature in Mussolini's Italy. Both Hall and Troubridge had difficulties in their relationship, such as Hall's infidelity and Troubridge's overly controlling attitude towards Hall.

In many ways, the pair subvert expectations of politically radical or even feminist lifestyles audiences might have for a pioneering lesbian author and her partner. While same-gender relationships between women were not illegal in the UK (unlike those between men), the pair still faced discrimination and unfavorable attitudes towards queerness, particularly when queer women lived as relatively openly as Hall and Troubridge did. While bohemian aristocratic groups (such as the popular Bloomsbury Set) held much more liberal views on gender and sexuality, their leftist politics and disregard for gender norms were antithetical to Hall and Troubridge, who were both politically and socially conservative and disliked those who they regarded as the embodiment of decadent modernism.

This teaching guide seeks to tell a story about two people who remain simultaneously beloved and questioned in queer communities. Many lesbian scholars still point to Hall's work as deeply influential. Many transgender readers see familiarity with the fluctuating and inconcrete categories of gender in Hall's work and personal beliefs. Troubridge's life after Hall's death, documented with scores of letters she wrote to her dead partner, allow insight into not only her role in shaping Hall's legacy, but also her own talents and interests as a sculptor, translator, and patron of the arts.

Similarly, this guide does not shy away from the complicated and sometimes disturbing aspects of their lives and personalities. From their political views to interpersonal behaviors that bordered on abusive, their choices as people and disregard for the human casualties of their beliefs likewise divide queer readers as to whether or not their works and biographies are worthy of fond remembrance. While this guide does not endorse one view over the other, it does seek to give educators and students the opportunity to approach those questions with the information necessary to formulate answers for themselves. This introductory section provides a biographic overview of both Hall and Troubridge, whose personal papers make up the foundation of this teaching guide. It provides biographical and historical context that seeks to go beyond a hagiography and engage more deeply with contemporary debates about Hall's and Troubridge's lives and works.

The Problem with Hall: a Summary of Methods and Pedagogical Choices

While queer history is long and nuanced, much of what is officially documented about queer people appears relatively recently. Laws, cultural conventions, and personal beliefs leave queer historians with a complicated task when it comes to sorting through intricate, delicate, and deeply personal information in the lives of long-dead people. This is certainly not easy work. Many of the decisions archivists, educators, biographers, and scholars make are difficult, thorny, and open to criticism. Each choice made means the rejection of another choice. In many cases, these choices are political. For example, many words and terms we use to describe queer relationships and a range of genders are also relatively recent. While queer and transgender people (to use contemporary parlance) have always existed, the vocabulary modern audiences might use to describe them have not. How does one refer to a long-dead queer person who self-described as a "woman trapped in a man's body?" While it is possible that such a person might identify as a transgender person in the present, it is also possible they would not. The decision to label them as transgender is innately difficult, with different transgender historians advocating for and against the appropriateness of such a choice. Below is a brief overview of the methods and approaches taken when constructing this teaching guide. All of them should be read as an invitation for discussion with the understanding that all choices were difficult and the ultimate decisions complicated and imperfect. Educators might benefit from posing these questions to students as they approach this teaching guide. Similarly, students could and should question what decisions they might have made if given the opportunity.

Radclyffe Hall, Letter to Evguenia Souline signed "John," July 31, 1934.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 46.5Hall used the name "John" in more familiar writing to friends and partners. The intimate term is particularly interesting to queer theorists. Hall approached questions of sexuality and gender through a lens of "inversion," a term that encompassed any out-of-place sexual or gender identities in the time in which Hall lived and wrote. Publicly and professionally, Hall used the name "Radclyffe" and publicly identified as female. There were documented examples of people who today we might describe as transgender living their lives unambiguously in contrast to their assigned gender at birth. People assigned female adopted masculine names, used masculine pronouns, and lived much of their adult lives as men. In those situations, decisions about pronouns, names, and identities are easier to make, as such choices would adhere to how that person lived and identified.

Hall, assigned female at birth, did not seem content to live within the gendered expectations of Victorian "womanhood" (though she did believe deeply that others should) and many - although not all - queer biographers, historians, and literary scholars have read her writing and biography through a transgender lens.

Similarly, many trans people might likely identify with some of the ways Hall describes the restrictions of gender. This teaching guide also recognizes the significant value and importance Hall has to lesbian readers and scholars, for whom Hall's identity as a lesbian woman is also significant.

For the purposes of this teaching guide, Hall will largely be referred to by last name. Referring to Hall as "John" would indicate a level of intimacy and familiarity that Hall seemed protective of in private writings. When a full name is used, it will be as "Radclyffe Hall," as this teaching guide is intended for a public audience. This is done with the recognition that such a choice is difficult and debatable. Transgender people often choose names that better fit their personalities and genders, and Hall's use of the masculine name "John" could fit within an identifiable pattern of chosen name vs. "dead name" (a name that one is assigned at birth, but abandons later for something more in line with their gender identity). However, it is impossible for historians to know what choices Hall would make in the present day. As such, this guide does not wish to make those choices for Hall.

The question of pronoun usage even in the present can be complicated and changeable (with many queer people using a range of pronouns until they find the most appropriate one). While historical record does give us people from the past who used pronouns at odds with their assigned sex at birth, Hall undeniably identified as a woman when it came to political issues (such as suffrage and debating gender roles). Nothing in Hall's writing indicates a preference for pronouns other than she/her. While there is no way to know what pronouns Hall might use in the present, using "they" or "he" pronouns in the teaching guide assumes too much editorial authority when it comes to posthumous gender assignment and negates the personal choice of living transgender people to select the pronouns that match their genders. Furthermore, to disregard "she/her" pronouns also erases the political aspects of living a woman in a deeply sexist society that Hall experienced, voiced, and occasionally endorsed. The process transgender people undertake of choosing pronouns that correctly match gender identity is a brave and often fluctuating act, and we recognize that many who might interpret Hall as being a gender besides a cisgender woman might find this decision painful. This is by no means an end of debate on how pronouns should be used for dead figures who some might read as transgender. However, as Hall never publicly identified as transgender nor used pronouns other than she/her, this teaching guide will adhere to those strictures while naming and recognizing that it is an imperfect and potentially hurtful solution.

Unidentified photographer, Two actors, one in drag, pose on garden furniture, 1918.

Wellcome Library 2043455iFor the purposes of clarity, certain terms used in this collection need contextualization.

Generally speaking, LGBTQIA+ scholars have used the terms "queer" and "queerness" in recent years to broadly describe sexualities and genders existing outside of cisgender and heterosexual identity. Despite its history as a slur in American English, "queer" offers space for a spectrum of sexualities and genders that might not easily fit within less flexible definitions. While this term is also ahistorical for describing the lives of people like Hall and Troubridge who would not have used it, it offers space for multiple interpretations on the parts of readers and does not seek to strictly categorize genders and sexualities that cannot be easily compartmentalized. For example, the artifact here, a postcard featuring two actors (with one in drag) might be described as queer. While we do not necessarily know the context in which the postcard was made, it breaks from cisgender and heterosexual practices, opening it up to a "queer reading."

Hall and Troubridge used the term "inverts," a term popular with sexual psychiatrists and researchers during their lifetime to describe anyone whose gender and sexuality did not match what modern readers might describe as cisgender and heterosexual identity. When it is historically appropriate, the teaching guide will use the term "inverts" for purposes of context. However, its highly medicalized nature would be contentious in contemporary queer spaces, where many queer people have worked actively to shake off institutional terms and overly-medical definitions for different genders and sexualities.

Lastly, this guide does not wish to shy away from the term "lesbian." Many lesbian scholars and readers use the term to not only describe a relationship between two women, but also as a political statement that rejects patriarchal norms and seeks to position women's sexuality outside of male influence and control. Hall and Troubridge both had a complex relationship with patriarchal norms. While they lived as two women in an emotional and sexual relationship, their personal and public writings are often more favorable to traditional gender roles and a rhetorical reliance on "exceptional" women than one might imagine. However, the use of the term "lesbian" seeks to honor the contributions of lesbian authors, readers, and scholars who have long defended The Well of Loneliness and its author and insisted on its historical and cultural significance.

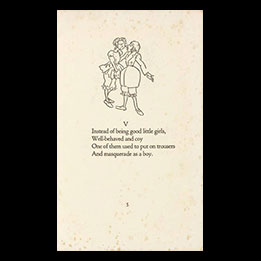

P. R. Stephensen, The Well of Sleevelessness (London: Scholartis Press, 1929).

University of London Senate House Library PR6037.T255|bW4 1929The question of queer privacy when it comes to the archive is, again, not easily answered. For many queer people, public discretion and an ability to have a separate "private" life was often the only protection they had from jail, social stigma, or even physical violence. Often, we are only able to find unambiguous evidence of queer identity in papers and documents the authors guarded with fierce privacy. Hall and Troubridge, not living in a state of financial or social precarity, took less of a risk than others might by living relatively openly in their queerness. However, the choice to expose personal letters, documents, and artifacts is a political one that often directly challenges the concept of posthumous privacy.

That being said, this teaching guide often relies on the narratives of queer people who were only revealed to be queer to the general public after their deaths. The fact that Hall and Troubridge lived relatively openly as lesbians in their lifetimes makes this challenge less contentious. As their sexualities were well-known and appear unambiguously in Hall's published work, the contents of their private letters does not risk "outing" them. However, other authors present more challenges. In terms of methods, this guide seeks to follow a system of creating dialogue that recognizes the broadness of queer scholarship and research methods. It uses queer feminist research methods that break from duplicating harm and patriarchal, queerphobic institutions. This method attempts to put historical figures in the context of their lives while not giving them a free pass for harmful beliefs and actions. However, these methods also center that the standard of behavior for historical figures from marginalized communities is much higher than for those who lived with more access to power. As such, this teaching guide makes the decision to engage with material and scholarship that are already publicly available and engage with queer figures and authors who are already understood as "queer." It does not "out" any new authors, regardless of whether they are alive or dead. However, it does not uphold a cisgender-and-heteronormative worldview that all people are cis and heterosexual until proven otherwise. It leaves room for readers to develop their own questions about artifacts and should be seen as an invitation for conversation rather than any authoritative guide. It simply seeks to provide archival material that might be useful when it comes to thinking about the legacies of Hall and Troubridge and context around not only their creative work, but of other queer authors and artists.

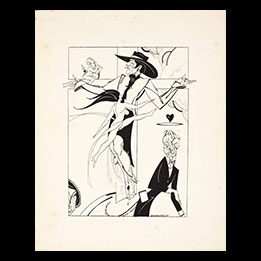

Beresford Egan, The Sink of Solitude (London: Hermes Press, 1928).

University of London Senate House Library 741.5942|219This teaching guide has an expressed goal of not shying away from disturbing and difficult content. Queer history and archival practices are not aided by writing overly charitable depictions of imperfect people, and, as such, this teaching guide seeks to critically examine less favorable aspects of both Hall's and Troubridge's lives and creative works.

Similarly, this guide acknowledges that homophobia often manifests through holding queer people to higher standards than cisgender and heterosexual people who shared similar beliefs and behaviors. This guide seeks to work against that trend as well, adding context to certain beliefs and tropes that appear in Hall's and Troubridge's papers while also bringing to light their racist and classist beliefs, horizontal oppression towards other women, or their reactionary politics.

When Una Met John: Partnerships and Fidelity

By the standards of the upper-middle class, Radclyffe Hall did not enjoy an especially pleasant childhood. Her wealthy father abandoned her in infancy and left her in the care of a deeply self-centered and resentful mother. Not particularly well-educated even by the gendered divides of the time, Hall quickly realized her considerable wealth gave her a degree of independence. She would never have to think about marriage or working a job, and, as such, she dressed as she liked. Believing herself more "man-like" in accordance with gender expectations of the time, she fancied herself a solid businesswoman, valued her assertiveness, and began acting on her attraction to women by the age of 17 (Vargo).

Una Troubridge grew up in genteel poverty, the child of a family who lost their fortune, but maintained a respectable name. Unlike Hall, she was relatively well-educated, having attended the Royal College of Art in 1907 and shown an aptitude for sculpting. Marrying a much older man to stabilize her family's income after her father died, Troubridge found herself quickly in an unhappy marriage where she felt little chemistry with her partner, Ernest Troubridge.

While Hall's and Troubridge's relationship with each other became the defining partnership for both women, it was certainly not an easy one. The two began an affair while both partnered to other people, deeply hurting and betraying their partners in the process. Furthermore, their partnership experienced additional long-term strain when Hall began an affair with Evguenia Souline, a Russian nurse.

While Troubridge remained partnered to Hall and seemingly blamed Souline for the affair, she too felt deeply hurt and betrayed by Hall's relatively open pursuit of Souline. Hall, for her part, was not against using her considerable wealth to control those around her. She frequently gave allowances to her partners, and, more problematically, would threaten to withhold money if they did not do as she pleased. She left multiple written records of veiled insinuations that she would disinherit Souline if she did something that very much displeased her (though she would ultimately leave her entire estate to Troubridge).

Troubridge, for her part, was deeply controlling of Hall, restricting her access to others, making unilateral decisions about her health, and indulging her with food and drink she requested against the advice of her doctors when her health began deteriorating in the final years of her life. Even after Hall's death, Troubridge exerted disproportionate control over Hall's estate and memory. She turned her ire towards Souline, minimizing her role in Hall's life as she began constructing a biography of her dead partner and writing letters to the now-dead Hall in which she attempted to reconstruct a deeply flattering depiction of their partnership.

To some degree, this section seeks to tackle the impossibly high standards that queer relationships are held to. Educators and students might question what metrics are useful when it comes to analyzing complicated biographies and determining what bearing someone's personal life has on how their creative work is understood. Like all relationships, Hall's and Troubridge's had its difficulties, aided by the less appealing aspects of the personalities of both women. Their relationship was indeed loving and significant to both Hall and Troubridge, who depended on each other and shared a life together. However, this section also seeks to examine the less flattering aspects of a relationship that was at times strained and how that relationship influences their legacies and biographies.

Unidentified photographer, Mabel Batten posing with pet dog and bird, before 1916.

Wikimedia CommonsHall met the celebrated vocalist Mabel Batten in August, 1907. 24 years Hall's senior, Batten represents the first long-term queer relationship of Hall's adult life. Nicknamed Layde, Batten had a profound influence on Hall, encouraging her conversion to Catholicism, giving Hall the nickname "John" she would use as an intimate moniker for the rest of her life, and introducing her to a wider social circle of queer women (Cline 58-67).

Hall and Batten began living together after the death of Batten's husband, and the two lived a relatively eventful social life, attending plays, opera, reading prolifically, and, for Hall, publishing poetry and short creative work (Hamer 94).

Of further influence was Batten's role in introducing Hall to Una Troubridge (Batten's cousin) in 1912. Unfortunately for Batten, the young, energetic Troubridge and Hall found themselves deeply attracted to each other. With Batten's health failing, Hall remained with her, but began an affair with Troubridge in 1915, a situation which deeply disturbed and hurt Batten, who died the following year.

Unidentified photographer, Mabel Batten and Radclyffe Hall posing with their pets, before 1916.

Wikimedia CommonsHere are Batten and Hall with several of their pets.

Both Hall and Troubridge felt some degree of guilt over their affair, with Hall privately believing the grief of it had hastened Batten's death prematurely. Hall and Troubridge, now living together, began to attend seances in hopes of reaching the now-deceased Batten from beyond the grave.

Though Hall would live with Troubridge until her own death in 1943, she would eventually be buried next to Batten in Highgate Cemetery in London. Troubridge, whose written wish to be buried with Hall was not seen until much later, was buried in Rome after her death in 1963, one month prior to the 20-year anniversary of Hall's passing.

Bassano Ltd., photographers, Ernest Troubridge, 1911.

National Portrait Gallery, London NPG x84932Una Vincenzo married Ernest Troubridge in 1908. He was a naval officer 25 years her senior, and she married him to stabilize her family's precarious financial situation after the death of her father. Una, known for her excellent skills as a host and conversationalist, was well regarded in her husband's social circles. While their marriage was initially warm, the two never enjoyed a gratifying sexual relationship, and she sought professional help to aid in their marital problems.

The pair welcomed their first and only child in 1910: a daughter named Andrea. By the time Troubridge began her relationship with Hall in 1915, their marriage was beyond repair. They separated four years later, and Ernest Troubridge died in 1926 (Hamer 94). His status as a naval officer, however, made him influential in many social circles. Several of his friends would attempt to professionally impede both Hall and Troubridge for years after the marriage fell apart.

Unidentified photographer, Evguenia Souline, undated.

Book Collection PR 6015 A33 Z62 1997bHall and Troubridge hired Souline, a Russian nurse, to care for Troubridge after she fell ill with a digestive illness in the early 1930s. Hall and Souline soon began an affair which, as with Batten, caused Troubridge significant mental anguish and pain. Unwilling to separate from Hall, Troubridge coped with the on-going affair, though doing so required a tremendous amount of emotional repression and a posthumous reappraisal of her relationship with Hall that at times bordered on delusional.

Hall's relationship with Souline, while deep and intimate, was not without trouble. Hall frequently threatened to provide financial support for Souline only if she did as Hall demanded, often threatening to disinherit her over what Hall perceived to be infractions or disobedience.

Una Troubridge, "To The Executors of My Will," September 23, 1944.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 36.1Una Troubridge pairs her personal acrimony for Souline with perhaps overly effusive praise for the deceased Hall in this letter related to Hall's wishes as she died of cancer in 1943. While Hall initially made provisions for Souline in her will, she revoked it on her deathbed in favor of Troubridge, who gave only a small amount of money to Souline (one year, she sent her a 5 pound note as a Christmas gift) (Souhami). When Souline was later dying from cancer, Troubridge refused to pay her medical bills, inquiring why she could not simply rely on the British National Health Service for treatment (Souhami).

In this letter, she details the destruction of diaries and other "evidence" related to Souline's and Hall's relationship that she felt might be improperly used. Considering Troubridge's significant role in posthumous publications about Hall and shaping public memory of her former partner, the deeply painful affair between Hall and Souline seems to be something she wished to quite literally erase from existence.

In this endeavor, Troubridge was unsuccessful. Souline preserved her letters from Hall, and their records detail a relationship more significant and meaningful to Hall than Troubridge would have liked those outside the relationship to believe.

Una Troubridge, Notebook entry on Nicola Rossi-Lemini, undated.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 34.1Memories of Hall and her personal antipathy towards Souline did not exclusively occupy the two decades of her life that Troubridge spent as a widow. She developed and sustained a deep friendship with the opera singer Nicola Rossi-Lemini and his wife, the Romanian soprano Virginia Zeani. Acting as what she believed to be a maternal, stable figure for "Nika" (as she called him), Troubridge followed his career around the world, watching his performances, frequently spending time with his family, and purchasing costumes for him. She gifted him Hall's sapphire cufflinks, and aided him by acting as a confidante, answering his fan mail, and using her skills as a translator to transcribe lyrics from English to Italian when necessary (Souhami).

Flouting Convention, Conventional Flouting

While the publication of and subsequent controversy over The Well of Loneliness dominates discourse of Hall's life, her personal life and beliefs offer a portrait of someone who deeply admired and aspired to upper class conventions of the day with her partner Una, Lady Troubridge. Modern-minded people in some regards (such as their interest in scientific innovations and politics), the couple openly professed a complicated and intricate system of beliefs that in many ways mirrored the same conventions that critics would accuse Hall of attacking. These documents are designed to challenge an overly simplistic and inaccurate view of Hall and Troubridge as those seeking to disrupt a conservative culture still deeply invested in Victorian convention. Their identities as queer people did not necessarily divorce them from the expectations of the social classes in which they grew up. If anything, their biographies reveal some degree of admiration towards the conservative and conventional when it came to positioning their respective lives in a favorable light by the standards of pre-World War II British society. Educators and students can consider the ways in which the pair held many of the conventional beliefs that came with the privileges of whiteness and wealth in a culture that rewarded both. However, as queer people, the pair also experienced some degree of precarity in relation to their surroundings. How do contemporary readers examine the ways in which the imperfections and prejudices of a culture manifest themselves in the writings of those we view as being outside of such belief systems? What impact does that have on the legacy of authors? Would we hold heterosexual authors to the same standards or as easily expect them to be iconoclasts?

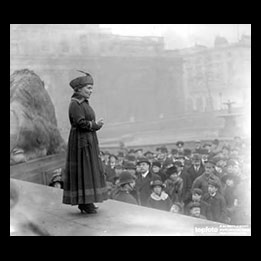

Unidentified photographer, Emmeline Pankhurst at the war meeting in Trafalgar Square, February 24, 1917.

TopFoto 3062181 / EuropeanaHall was an occasionally strained supporter of the suffrage movement. However, like many upper middle-class suffragettes, Hall's vision for women's right to the ballot was more a responsibility for wealthy women rather than a rallying cry to bridge the political divides between women of all different income levels.

Emmeline Pankhurst, pictured here, eventually advocated property destruction (such as breaking windows and blowing up mailboxes) as political tools for securing the vote for women. Hall, outraged by Pankhurst's tactics, wrote an anonymous letter, stating, ''According to Mrs. Pankhurst, they are resorting to the methods of the miners! Since when have English ladies regulated their conduct by that of the working classes?'' (Mallon, 1985).

Hall was certainly not unique amongst her class when it came to such an opinion. Furthermore, British suffragettes used the fact that indigenous women were voting in New Zealand to stress their perceived outrage of non-white women voting while white British women went without. However, rather than offer a picture of women's suffrage in the United Kingdom as a unified effort looking to secure the vote for all women, Hall's limited endorsement of the right to vote illuminates how class and loyalty to convention complicated the history of the British suffrage movement.

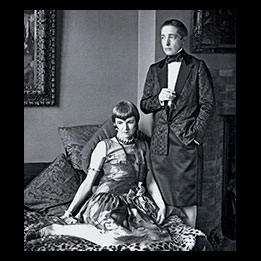

Fox Photos, Radclyffe Hall with Una Troubridge, August 1, 1927.

Hulton ArchiveHall and Troubridge at least publicly endorsed the notion of gender roles in a marriage, regardless of sexuality or gender identity. During a pair of interviews with the lesbian journalist Evelyn Irons, Hall described her relationship with Troubridge as relatively in line with the conventional standards of British domesticity at the time. However, in her second interview (entitled "Woman's Place is the Home"), she divides women into two categories: the conventional and the exceptionally talented "potential Amazon" (Jagose).

It is, of course, possible that the public presentation of a relatively conventional marriage agreement between Hall and Troubridge did not match reality. Furthermore, due to the proximity of these interviews to the debut and controversy surrounding The Well of Loneliness, publicity generation might have motivated their appearance. However, it does portray at least some awareness of gendered expectations within a marriage between the pair that did not greatly challenge social conventions of the day.

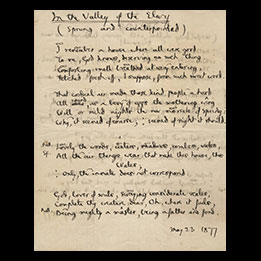

Gerard Manley Hopkins, "In the Valley of the Elwy," May 23, 1877.

Gerard Manley Hopkins Collection 1.1Like Hall, Gerard Manley Hopkins was an English Catholic with deeply-held religious beliefs. Hall and Troubridge followed Catholic church politics throughout their lives, with both expressing support for Pope Pius XII, commending him for his good relationship with Mussolinni, and attending his coronation mass in 1939.

Hall converted to Catholicism in 1912 under the influence of Mabel Batten (who kept photographs of the Pope in her bedroom when she became too ill to attend mass), her partner and herself a Catholic convert. Troubridge, too, converted to Catholicism. For Hall, Catholic themes and deep belief in spiritual responsibility appear regularly throughout her work as she sought to reconcile her seemingly contradictory status as a Catholic queer person. Stephen, for example, compares "inversion" (a broad term for anyone who did not adequately perform gender and sexual behavior) to the mark of Cain from Genesis in The Well of Loneliness.

While perhaps unusual-sounding to modern readers, Hall and Troubridge both belong to a relatively populous history of famous queer Catholics, including Oscar Wilde and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Furthermore, other queer authors, such as Henry James and Willa Cather, relied deeply on religious themes as framing devices in their works.

A Jesuit priest by training, Hopkins's religious poetry contained deeply homoerotic undertones and his private letters indicate a desire to suppress his own sexual thoughts through his writing (Edge, The Guardian).

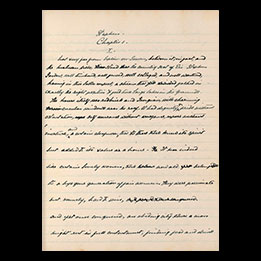

Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness, manuscript, undated.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 13.1Sharing her name with the first Christian martyr, the Catholic Saint Stephen, Stephen Gordon (the protagonist of The Well of Loneliness) is both deeply religious and drawn to sexual psychiatry as orienting forces when it comes to understanding her lesbian desire.

While Hall's biographers debate the degree to which readers should understand Stephen Gordon as an autobiographical reflection of Hall, Stephen undoubtedly shares Hall's deep spiritual interest in Catholicism, seeking to pair it with early twentieth-century discourses in medicine around sexuality and gender identity.

Unidentified author, "Lady Troubridge's Feat," clipping in scrapbook. May 7, 1922.

PEN (Organization) Records 112.7Hall and Troubridge were both members of PEN International. Founded in 1921, the organization seeks to protect free expression and the open exchange of ideas.

For Hall and Troubridge, this network would prove useful during The Well of Loneliness's trial, as several other members of PEN rushed to their defense.

However, their membership in PEN and commitment to free expression seemed contrary to their support for the censorship of anti-fascist literature during their time in Italy.

Radclyffe Hall, "Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself," manuscript, undated.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 19.1Hall's insistence that she spoke for "misfits," is largely a self-awarded distinction. Certainly sympathizing for her protagonists, such as Stephen Gordon and the titular Miss Ogilvy, Hall's understanding of misfits did not extend much further than those outcasts with whom she personally identified.

Eugenics, a pseudo-science that held only certain people were "fit" to reproduce due to their superior genetics, permeates the queer sexualities Hall describes. To be sure, Hall was one of many who gave credence to the idea at the time. In Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself, seen in the image, Hall positions "inverts" as valuable members of society who could, Hall argues, contribute to reproduction and the protection of superior races (Funke). If inverts could reproduce, Hall argues, they would be valuable assets on the frontlines of protecting genetic purity rather than be the threat to the future that eugenicists argued they were.

In this regard, Hall's work at times teeters towards a queer anti-radicalism. Rather than reject cultural demands of women like motherhood and reproduction, Hall holds out hope that inverts - if they were only to be accepted - could contribute to the same culture that oppressed them.

"A Born Fanatic"

Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge were both people of strong opinions. Troubridge referred to Hall as a "born fanatic." Undoubtedly Hall did not shy away from controversy, nor was she hesitant to let her views be known to those around her. That outspokenness leaves behind a relatively well-documented legacy of political beliefs for both Hall and Troubridge. The accusations of Hall and Troubridge being "soft supporters of fascism" are understated. While references to Hitler appear in their writings in relatively neutral terms (with Hall saying he only wanted "justice" and commending him for keeping order in Czechoslovakia and other small countries she regarded as an "awful menace") (Suhami), they were indeed committed fascists. Of higher esteem in their opinions was Italian Fascist Benito Mussolini, who Troubridge described as a "genius and a good man," (Suhami). Of course, Hall and Troubridge were not alone in their problematic admiration for Mussolini and their bigotry and fear towards those they deemed inferior. The American poet Ezra Pound, for example, likewise publicly admired Mussolini and professed antisemitic views (as did T. S. Eliot, a contemporary of Hall's and frequent collaborator with Pound). Gertrude Stein (herself a Jew and a lesbian) infamously offered to serve as a propagandist for the Vichy French government (a Nazi puppet state). However, to disregard or trivialize Hall's and Troubridge's involvement with fascism (to the point of suppressing the freedom of the press), vocal antisemitism, and political support for eugenics would paint an incomplete portrait of two women who held far-right political views and more than once used the weight of their celebrity to serve on the side of fascism. Educators might ask students what role personal politics play in one's writing or if it is even possible to divorce political beliefs from themes in writing. Students might, in turn, think about how the realities of Hall's and Troubridge's political beliefs complicates or does not complicate their legacies. What roles do white supremacy, racism, and a sincere belief that certain people were inherently and genetically superior to others play in the biographies of the two women and their positions as significant queer historical figures?

Unidentified photographer, Fascist salute to the Italian flag, undated.

Promoter Gallery 285/ EuropeanaHall and Troubridge flew the Fascist flag and Union Jack outside their Florence home while living in Italy before the outbreak of World War Two forced them back to the United Kingdom, where Hall would die in 1943.

Unidentified artist, "La Via Del Mar Rosso Un Mare Rosso Di Sangue," 1944.

U.S. Holocaust Museum 2016.184.561"Yes, I am beginning to be really afraid of them, not of the one or two really dear Jewish friends that I have in England, no, but of Jews as a whole. I believe they hate us and want to bring about a European war and then world revolution in order to destroy us utterly," Hall wrote to Souline while she and Troubridge lived in fascist Italy (Suhami). Hall certainly knew Jewish people, including the ones she references. Leonard Woolf, a Jewish man, had been one of her public defenders during The Well of Loneliness's public trial.

Antisemitic beliefs were not uncommon in the upper-middle class social circles in which Hall and Troubridge would have lived, but the casual stereotyping of Jews as power-hungry and sneaky seems to give way here to an even more sinister depiction of Jews as seeking to destroy the world and, Hall feared, eliminate Christianity. Such were frequent tropes anti-semites used in propaganda. While the Italian fascists were less hostile to Jews than the Germans and did not begin seriously restricting the rights of Italian Jews until 1938, the Nazi puppet state established after Mussolini's deposition in 1943 murdered over 7,000 Jewish Italians.

The Italian Nazi puppet state crafted this poster in 1944. A piece of antisemitic propaganda, it plays on similar fears to the one Hall describes in which Jews are money-hungry war mongers out to capitalize off of European conflict.

James Agee, Statement on Ezra Pound, manuscript, undated.

James Agee Collection 8.12Author James Agee comments on the complicated legacy of Ezra Pound as both poet and public fascist sympathizer and anti-semite. Pound spent over a decade of his life in psychiatric care, after making radio broadcasts for the Nazi puppet state in Italy where he supported eugenics and fascist anti-semitism in hundreds of addresses he composed before being arrested for treason. Agee's statement seeks to address similar questions that this teaching guide touches upon. While Hall's and Troubridge's relationship with the Italian fascists was not as deep or sustained as Pound's, the question of how politics influence how one's writing is appraised proves difficult to answer for Agee, who composed this while Pound was still living.

Valentine Ackland, "Reflections at the telephone," manuscript, undated.

Genesis: Grasp Collection 1.11The Spanish Civil War divided British sympathies between fascism and communism. The lesbian poet Valentine Ackland and her partner, the short story author Sylvia Townsend Warner, were members of the Communist Party. Like Hall, Ackland typically dressed in masculine clothes, wore short hair, and rejected her feminine birth name for something more masculine. Like Hall, she engaged in an extended affair (with American author Elizabeth Wade White) that caused her partner considerable pain. Like Hall, she spent her final years critically ill from cancer. Like Hall, she had been a Catholic (though later left the church to become a Quaker). Her personal politics brought her under close scrutiny from the British government, and her work went unread until it experienced a revival during the 1970s in lesbian-feminist literary circles.

Her confessional style of poetry fit in more neatly with the leftist British literary circles that clashed with Hall's more conservative views.

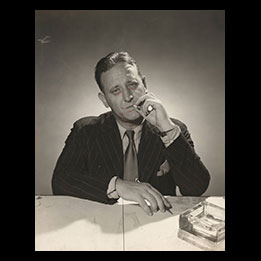

George Platt Lynes, photographer, John Gunther, undated.

George Platt Lynes Collection 2002:0045:0016John Gunther's Inside Europe was banned by the Italian fascists for its portrayal of Mussolini's government. While living in Fascist Italy, Hall and Troubridge subscribed to an English library run by Lillian Baird Douglas, who, Troubridge learned, stocked books banned by the government, including Inside Europe.

Despite Hall's and Troubridge's intimate relationship with the censorship and hostility surrounding The Well of Loneliness just a decade before and despite the pair's membership in PEN, an organization dedicated to free expression, Troubridge promptly reported Douglas to the authorities for publishing a banned book and ruined Douglas's reputation by accusing her of being an alcohol and morphine addict (Suhami).

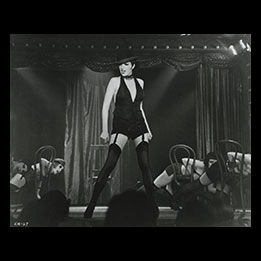

Unidentified photographer, Liza Minnelli in Cabaret, 1972.

Film Stills Collection CA-27Based on gay author Christopher Isherwood's Goodbye to Berlin, the musical and subsequent film Cabaret examines the rise of fascism in Nazi Germany through the prospective of a queer writer living in Weimar Berlin as the increasingly sinister objectives of Hitler and the Nazi Party become clear.

Takedown Notice: This material is made available for education and research purposes. The Harry Ransom Center does not own the rights for these items; it cannot grant or deny permission to use this material. Copyright law protects unpublished as well as published materials. Rights holders for these materials may be listed in the WATCH file. It is your responsibility to determine the rights status and secure whatever permission may be needed for the use of any item. Due to the nature of archival collections, rights information may be incomplete or out of date. We welcome updates or corrections. Upon request, we'll remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. The unpublished works, correspondence, diaries, and daybooks of Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge are under copyright in the United States. The Ransom Center is grateful to Alessandro Rossi Lemeni Makedon, the representative of Troubridge's estate, who has granted permission for the Center to share the papers of Troubridge.