Hall-Troubridge Teaching Guides

These guides have been developed to provide resources to instructors interested in teaching with the Hall-Troubridge Digital Collection and to offer students the opportunity to engage with archival resources to enrich their learning experience.

Lavender Ink: Introduction to Writing and Publishing Queer Literature

What makes literature "queer?" Did Truman Capote write queerness into the frozen Kansas veldt in the pages of In Cold Blood by simple merit of his personal life? How do Claude McKay's alligator pears and ginger roots in The Tropics of New York offer a lens for queer literary scholars to apply a queer-of-color analysis? What about people like Radclyffe Hall whose depictions of queer characters aged poorly and even drew ire in the author's time for unflattering depictions that may play into social stereotypes?

To say we must approach that question gingerly would be an understatement. The lives and works of queer authors did not always yield unambiguous depictions of queer people in their literature. Similarly, laws about what could and could not be published and which people could and could not form romantic and sexual relationships made the process of writing queerness even thornier.

While queer theory as a lens through which one can read literature gained in popularity after the late 20th century, literature scholars have not yet reached a consensus on what counts as queer literature or even who counts as a queer author. In this category, we navigate that difficult path while leaning in on that ambiguity and highlighting artifacts that demonstrate how enormously difficult and delicate this type of work can be for literary scholars and historians alike.

The intimate politics of interpersonal relationships gave control of estates to people like Una Troubridge, who outlived her partner and wanted to present a posthumous version of the woman she loved as she saw her to the world. That meant deliberate erasure of people and events that represented painful parts of her relationship with Hall. Herself no stranger to publication, Troubridge represents what many queer biographers with extreme personal interest in those about whom they wrote navigate: telling a queer story to a world that would likely be unsympathetic and not fully understand the relationships described.

Of course, other intersecting factors of race and income already presented barriers to queer authors of color and those without wealth. For them, the act of writing queerness proved even riskier. However, that did not stop them from alluding to their relationships in their personal and public writings. Their own struggles to advocate for their work is significant, as are the ways in which they had to navigate factors such as racism and classism in the publishing world that White, wealthy writers did not.

For educators and students alike, these artifacts offer us the chance to examine and question the world of queer authors and the compounding factors we must consider as contemporary readers of their work.

Defining queer literature and aethetics

As with much of literary analysis, questions about queer readings of texts are diverse and nuanced. While queer literature has existed as long as we have had literature, methods of evaluating the "queerness" of a text began to especially grow in an American context in the 1970s. Even then, the work of queer scholars from that point to the present day has drastically evolved as public understandings of gender and sexuality shift and fluctuate. This section invites students to form their own hypotheses of how they would determine queer themes in a text and provide a "queer reading." That does not mean all of these texts had openly queer authors or subject matter. However, considering that obscenity laws and social conservatism required authors to craft queer themes in their books with some degree of discretion, many literary studies practitioners maintain openmindedness and creativity when looking for queer subject matter. Other identities overlap as well in such readings. Queer-of-color critiques might center Black, Indigenous, and other persons of color queer narratives in their methods. Queer Crip scholars might look at how sexuality, gender, and disability overlap. Eco-Queer scholars might look at the environmental world and queerness in works of film and literature. As such, it can be a fun and exciting opportunity for those new to queer scholarship to think about what aspects of queer identity in literature interest them. This section is designed to give space to such thought and provide an introduction to the nuances of queer scholarship.

Guy Davenport, Review of We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson, December 31, 1962.

Guy Davenport Papers 35.8While it is not known if Jackson herself was queer, The Well of Loneliness, which she read as a student at the University of Rochester, certainly impacted her. Both flattering and unflattering depictions of lesbians certainly pepper her fiction, and it is known that she had openly gay friends. However, Hall's oblique references to her protagonist's sexuality in her famous novel could be and were interpreted through a lens of nonconformity. While Stephen may be a lesbian, the word "lesbian" during the time that Hall's and Jackson's lives overlapped was not fully understood in its contemporary context. While Jackson herself might not have been a lesbian and left no written or spoken clues she found women attractive, she felt some degree of identity with queer characters she encountered through reading, in the sense that they were both mutual outsiders.

For modern readers who examine literature using queer theory, Jackson leaves behind a rich legacy. She wrote queer characters, such as Theo (implied to be a lesbian) in the 1959 horror novel The Haunting of Hill House. Furthermore, her texts regularly depict the home, the nuclear family, and cultural expectations for women as horrific and violent. Similarly, her "misfit" characters play into many of the cultural expectations that queer people living in Cold War America likely felt. For students, it begs the questions: what do we define as a queer theme? What role does a text's popularity with queer readers play when it comes to making such an evaluation?

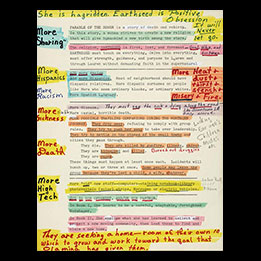

Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower, outline and notes, circa 1989.

Huntington Library OEB 1765By the time of her untimely death in 2006, Butler had given considerable thought to sexual orientation and gender. Pioneering and genius, her invaluable contributions to speculative fiction featured characters who shifted gender and bodies regularly and whose sexualities did not fit within White, European understandings of the words. For example, her 1980 novel, Wild Seed, features an immortal, African protagonist who shape-shifts to different bodies to ensure her survival.

Growing up in segregation-era America as a Black, disabled girl, she was drawn early to writing, particularly science fiction. She would go on to make contributions to speculative fiction and afrofuturist genres which challenge White-dominant cultural conceptions of what the future means and entails for people of color. Though speculation is still rampant (and inconclusive) about her sexuality, Butler's speculative universe offers a fluid, rich future in which to imagine queer identities and queer bodies of color without the cultural forces that would seek to marginalize them.

For students, it is worth considering how queer scholarship can take up questions of the "future" and how different understandings of bodies and desires might relate to alternate timelines and realities.

Marcel Proust, A l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, paste-up sheet, undated.

Carlton Lake Collection of French Manuscripts 314.3Marcel Proust has been a fixture of queer literary studies for decades. In Hall's The Well of Loneliness, Stephen travels to Paris, which Hall describes as a much more open, tolerant place when it comes to sexuality than the United Kingdom. This partially involved a relaxed legal system that did not criminalize homosexual activity. However, the titanic presence of Proust as a queer author who also incorporated queer themes into his texts cannot be understated in the literary universe in which Hall wrote. His iconic text, In Search of Lost Time, features several references to same-gender romantic and sexual desire, and is in many ways iconic of the Parisian queer literary scene in the early modern period.

An author of prodigious ability, Proust is still an influential figure in discourse on LGBTQIA+ literature and literary history.

Unidentified photographer, Yoshiya Nobuko, November 26, 1947.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Japanese feminist writer Yoshiya Nobuko wrote a series of semi-autobiographical stories for young women and girls that focused on romantic friendships in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Openly lesbian and commercially prolific as a writer, Yoshiya Nobuko lived openly with her partner, Monma Chiyo, who she later legally adopted as her daughter so the pair could have legal rights when it came to medical decisions and property transfer, a practice not uncommon for queer couples at the time.

Vandamm Studio, photographer, Noel Coward and Gertrude Lawrence in Private Lives, March, 1931.

Wikimedia CommonsA friend and collaborator of Radclyffe Hall's, Noel Coward in many ways epitomized queer British writing for several decades of the 20th century. Coward, with his witticisms and ostentatious persona, seems an unusual comrade to Hall's more somber and spartan style. However, the two were friends and collaborators throughout their lifetimes, and Hall possibly based a character in The Well of Loneliness on Coward. Private Lives offers a transcript of Coward's own stylistic choices as a well known, commercially successful queer playwright and actor. The title itself calls to mind the privacy of queer relationships and the subject matter, with its comedy-of-manners approach, fits within the legacy of other queer playwrights such as Oscar Wilde who made thinly-veiled references to their sexualities through their writing.

Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp, digital file, 1964.

Monoskop WikiThe concept of "camp" permeates queer literary analysis and scholarship. Though certainly present before Susan Sontag's 1964 essay, Sontag analyzed the work of several prominent queer authors, including Christopher Isherwood, to analyze and place the aesthetics of camp into broader academic discourse. Not merely "larger than life," Sontag describes "camp" as "the love of the unnatural." Though she describes camp as "apolitical" and not innately queer, the term has been largely associated with gay and bisexual masculinities. Drag culture, exaggerated acting in classic films, and the works of filmmaker John Waters all fit to varying degrees under the aesthetics of "camp." However, lesbian, transgender, and asexual literary scholars have pushed back on the erasure of non-gay men from camp categories and have attempted to theoretically position the work of transgender, lesbian, and asexual authors into frameworks of camp. Stylistically, Hall's suits and manner of dress might fit that category. Her literary aesthetic might also fit within a lesbian or transgender analysis of camp. How can scholars position Hall's work within a camp framework? Is this method of analysis still valuable? How might readers of Hall's work take up this term that has been so frequently described to many of her queer contemporary authors and historical figures?

Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness, manuscript, undated.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 13.4Hall's The Well of Loneliness offers a trove of entry points for queer literary analysis. Though typically held up as a watershed text in lesbian literature on par with Patricia Highsmith's The Price of Salt, transgender literary scholars also view the text with interest. The concept of "introversion" (broadly understood to mean inadequate complicity with gender constructs and norms), the protagonist assuming the name "Stephen," and the ambiguous lines between sexuality and gender identity offer rich lines of inquiry when it comes to imagining this text as transgender literature. While the term "transgender" might not have existed as we know it in Hall's time, literature dating back to the ancient times offers transgender literary studies a wealth of opportunities for analyzing social constructions of gender and transgressions against those norms.

Publishing while Queer

To say that the path towards publishing The Well of Loneliness was difficult would be an understatement. In addition to questions of obscenity and legal challenges against its content matter, Hall experienced extreme frustration that the question of the book's merit came down to "free speech" rather than Hall's skills as an author and what Hall believed to be the text's obvious literary merit. Hall was certainly not alone in that regard. Queer authors who published queer content prior to shifts in public culture and opinion in the late 20th century did so at extreme personal risk. While audience mattered and more progressive genres such as poetry and theatre offered queer authors slightly more overtness in content, the task of creating queer literature for broad public consumption was difficult and fraught. Many queer authors who published books and plays with unambiguous queer content did so anonymously. Others sought to incorporate queerness through symbolism and codes that queer readers might understand but that non-queer people might not. Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, while not overtly queer at surface level, relies heavily on the question of "double identities." Amy Lowell's poetry regularly used flower imagery to symbolize queer sex and intimacy between women. Mary Shelley's monster in Frankenstein (adapted for film by openly gay director James Whale) is given life through collaboration between men, sidestepping heterosexual reproduction. Others simply complied with social expectations for how queerness might be best received by the reading public. For example, cultural norms (such as the Motion Picture Production Code of 1934-1968) didn't explicitly ban queer characters and content, but did dictate that queer characters must be punished and not rewarded with a happy ending. Lillian Hellman's 1934 play The Children's Hour ends in a death by suicide, as does the queer husband of Blanche Dubois in Tennessee Williams's 1947 Broadway play A Streetcar Named Desire. However, queerness became a less taboo topic for authors with the shifts of the 1950s and 1960s such as the publication of the Kinsey Studies in 1948 and 1953, Betty Friedan's 1963 The Feminine Mystique, and queer uprisings at The Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in 1969, at Compton's Cafeteria in San Francisco in 1966, and at Cooper's Donuts in Los Angeles in 1959. However, that does not mean decades of European and North American morality culture disappeared overnight. This section places Hall's own challenges with publishing as a queer person in broader context with other authors throughout the early to mid twentieth century. Teachers might use this space to talk about symbolic readings of queerness, the importance of a "happy ending" for queer characters, and thorny questions about artistic integrity and cultural challenges to publishing queer works.

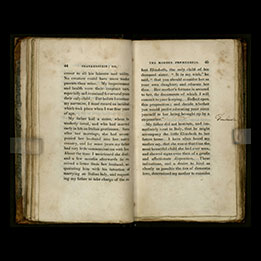

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The modern Prometheus (London: Printed for Lackington…, 1818).

Robert Lee Wolff Collection 6280Considered now to be a pioneer of both the science fiction and horror genres, Mary Shelley wrote her iconic text Frankenstein at age 20. Published anonymously (a relatively common practice in 18th- and 19th-century England to circumvent the sexism women faced when publishing), the book defined genre when it came to speculative fiction, but has also long fascinated queer literary and cultural scholars alike. Shelley's and her husband's (poet Percy Bysshe Shelley) sexuality remain controversial. Shelley, the daughter of proto-feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, certainly had queer friends (including Mary Diana Dods and Isabella Robinson), and her private writings allude to possible queer relationships with women after her husband's death. However, when it came to publishing, her text illustrates the delicate and difficult task of balancing an author's personal life with their creative work. Regardless of Shelley's own sexuality, the text challenges the "biology" of the body and sexual reproduction. Similarly, the Monster exists as an "outsider" in his world, hating his creator and seeking aimlessly for love and belonging. The novel later assumed another association with queer culture when gay director James Whale adapted it into the films Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein. Held up today as icons of queer cinema, the films highlight the transgressive approach to bodies and sexuality that Shelley constructed in her novel.

Patricia Highsmith, Letter to Jenny Bradley, March 5, 1960.

William A. Bradley Literary Agency Records 31.9Patricia Highsmith's pioneering 1952 novel The Price of Salt (adapted into the 2015 film Carol) notably featured a relatively happy ending for its two lesbian protagonists, an unprecedented inclusion in queer literature up to that point. Social conservatism around LGBTQIA+ identities resulted in most queer literature ending in tragedy, even when queer authors wrote them. Predominantly involved in romantic relationships with women, Highsmith is more widely known for her Mr. Ripley mystery books and published The Price of Salt under the alias "Claire Morgan" to preserve her career. Involved with leftist circles and vocally supportive of Civil Rights, her published diaries also demonstrate deeply problematic and complex flirtation with antisemitism.

Critically well regarded, the text avoided many of the challenges The Well of Loneliness faced (though the almost three decades between their publication might account for this). Like The Well of Loneliness, The Price of Salt is undoubtedly a titanic work of lesbian fiction and has gone through several successful rounds of new editions prior to being published for the first time with Highsmith's name in 1990.

Elizabeth Bishop, Letter to Anne Sexton. September 14, 1962.

Anne Sexton Papers 18.1This letter between poet Elizabeth Bishop and Anne Sexton features Bishop offering a stark, enthusiastic evaluation of Sexton's poems. Describing them as "harrowing, awful, very real, and very good," Bishop commends fellow New Englander Sexton's authentic voice and bold approach to gloomy subject matter. Bishop, fiercely private about her identity as a lesbian, actively avoided identifying as a "female" or lesbian poet and even refused to have her poems published in women-only anthologies. Though recognized as one of the most gifted poets of her generation, Bishop's own perfectionist tendencies limited her creative output to roughly 100 published poems. Sexton, married to a man, had several affairs with women, including her friend Anne Wilder.

Sexton's writing involved highly personal material and an emotionally charged response to typically "off-limits" subjects, such as her bouts of disabling mental illness, almost entirely antithetical to Bishop's more objective voice. However, she offers sincere and earnest praise on Sexton's work, even though she self-categorizes her work as "not objective" due to her ability to intimately recognize the details of a somber New England life hovering in the background of the poems.

Regardless, this letter encapsulates a specific and memorable interaction between two highly regarded and influential voices in American poetry. Both sought to be compelling, strong writers and to enhance their considerable talent through constructive feedback. It also centers the role of platonic and creatively enriching friendships between queer women as valid and important components of any queer biography.

Allen Ginsberg, reading "Howl," sound recording, 1959.

Sound Recordings PS 3513 I74 A6 1959A fixture of the Beat poetry movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the openly gay Allen Ginsberg published the poem Howl in 1956. Like Hall some three decades before, Ginsberg found his work on trial for obscenity after poet and publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti and City Lights Bookstore manager Shigeyoshi Murao were arrested and charged with selling obscene reading material after an undercover police officer purchased Howl. After a highly sensationalized trial, both were acquitted when a judge ruled the poem did not qualify as obscene. Howl, with its highly experimental style and unambiguous references to queer sexuality, remains a watershed text in American poetry and queer literature, and City Lights Bookstore still operates in San Francisco.

Claude McKay, Letter to Nancy Cunard, undated.

Nancy Cunard Collection 17.1Jamaican-American poet Claude McKay took exceptional risks as a poet when it came to style, meter, and political messaging. A devoted leftist for most of his early life, he defied suggestions that he "tone down" the more controversial elements of his poems and personal writings to comply with Jim Crow-era American expectations that Black authors write conservatively.

He writes here to the British writer and political leftist, Nancy Cunard. Cunard wrote in favor of the Civil Rights movement, writing essays that attacked white women's racism against people of color, edited The Negro Anthology, and received death threats too obscene to be published.

Compton Mackenzie, Foreword to Extraordinary Women, manuscript, 1953.

Compton Mackenzie Papers 22.2Just as The Well of Loneliness hit bookstore shelves, Scottish author Compton Mackenzie published his own lesbian-themed novel. Extraordinary Women is, however, a satirical piece that lampoons British lesbians and disregards the validity of their relationships (including several characters that mock Hall and several of Hall's and Troubridge's friends). Mackenzie's foreword to his book demonstrates his open contempt for The Well of Loneliness and how the sensationalism following its publication simply served, in his opinion, to make a "dull book" seem "exciting."

Pegasus Press, The Well of Loneliness, leaflet, 1928

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 17.2After the controversy and subsequent obscenity trial surrounding The Well of Loneliness, Hall expressed considerable frustration that those who came to her aid (including Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard) did so on "free speech" grounds rather than defending what Hall believed to be the book's obvious literary merit. What Hall regarded as skillful writing met with mixed reviews when it came to the actual content of the book. While there's no denying the text's importance when it came to publishing openly LGBTQIA+ content, even scholars and biographers favorable to Hall are still today divided on whether or not the text is well-written.

Queer Women and Ambiguous Sexualities

For many women who did not marry or lived lives outside of cultural expectations for women, questions about their sexuality persist. Pre-20th-century gender expectations in North America and Europe largely dictated separate spaces based on gender binaries. Doubtlessly, many women leave behind legacies of homosocial bonding in schools, seminaries, and social circles. Eleanor Roosevelt and Juliette Gordon Low both wrote about their "crushes" at their respective early-twentieth-century schools, and their papers still hold much important content for bisexual and lesbian scholars. Many queer women navigated space for themselves within these spheres, forming close friendships and sometimes sexual and romantic relationships with other women. That is not to say that all women authors who have lived and died without conclusively self-identifying as heterosexual would do so if given the chance. Many were queer, and it certainly does not make their work off limits for queer literary scholars. For example, while Harper Lee never conclusively addressed her sexuality and bristled when asked about it, her 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird is a popular text for queer analysis, with Scout's and Dill's ambivalent relationship with gender conventions continuing to produce rich discourse within literary scholarship.

For the purposes of Hall and Troubridge, sexuality in their time was largely defined based on the works of Sigmund Freud. Later twentieth-century authors and painters such as poet June Jordan, novelist Octavia Butler, and painters Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Georgia O'Keeffe would deliberately seek to reimagine cis-women and women's sexuality outside of a male-dominated Freudian discourse. For her part, Hall deeply believed in scientific innovations. However, her social circle and contemporary authors included many people who guarded their sexuality with fierce privacy, or at least never commented on their romantic connections in writing. Teachers might use this section to frame the inevitable question of whether how much we do or don't know about an author's personal life should influence how we read their work. Furthermore, a feminist inquiry into this section might question how transgressing gender expectations fits into a queer framework and why centering the relationships between women in literature remains a powerful and important thing. For students this might provide a spring-board to think about how much or how little an author's sexuality, gender identity, or other identity marks should play in how we read and understand texts, particularly when those personal questions don't necessarily have clear answers. Furthermore, how do we examine literature through a "queer" lens when it comes to analyzing love and same-gender affection in texts that might have had different understandings of sexuality than contemporary culture?

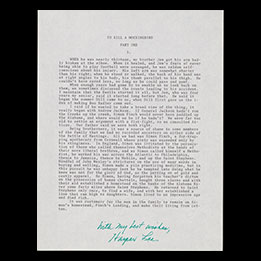

Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird, signed manuscript page, undated.

Truman Capote Collection 3.2Like The Well of Loneliness, To Kill a Mockingbird met with significant polarization. Highly popular, the book has never been out of print since its initial publication. However, it's themes about the segregated south opened the book to significant challenges, ranging from luke-warm reviews from prominent southern authors such as Flannery O'Connor, to being outright banned in many parts of the country. Similarly, Black authors and historians criticize the book's over-simplification of race in the South and for glorifying White moderates in the Civil Rights Era.

Here we have a signed typescript of To Kill a Mockingbird which Lee sent to her life-long friend, the openly gay Truman Capote. Lee's sexuality long fascinated readers of her Pulitzer Prize–winning book, much to Lee's annoyance and possible amusement. Given multiple opportunities in her life to address her sexuality, Lee never publicly identified as queer. However, queer readers have long identified with Scout and Dill (semi-autobiographically based on Lee and Capote) in the text, both of whom defy gender conventions in their Alabama town. While there is no way of knowing Lee's sexuality, significant speculation comes from the author's own disregard for cultural norms and conventions for women of her time.

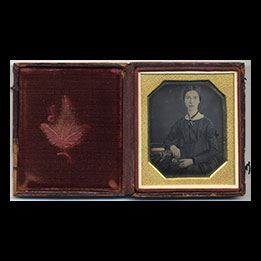

William Case North, photographer, Emily Dickinson half-length portrait, circa 1846-1847.

Amherst College Archives and Special Collections Series 3Remembered for her innovative and transgressive use of unconventional meter and subject matter, Emily Dickinson is now something of an icon in the pantheon of American poets. Though she is commonly caricatured as a ghostly, old-maid shut in, her private life was rich, captivating, and intimate. Her poems allude to close friendships, possible romantic interests, and her own questions about the natural world, romantic love, and mortality. Since Victorian-American understandings of gender typically involved entirely separate social spheres for men and women, romantic friendships between women were not uncommon, and Dickinson certainly had both male and female friends whom she regarded with deep affection. While we have no conclusive proof about Dickinson's sexuality, queer scholars express particular interest in her relationship with her sister-in-law, Susan Huntington Gilbert. Regardless, her work frequently appears in LGBTQIA+ anthologies, and queer analysis of her creative work continues to the present day.

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962).

National Museum of American History 2013.3104.01Scientist and author Rachel Carson became synonymous with her 1962 book, Silent Spring, which examined the harmful effects of DDT. She also was widely known in her lifetime for her work on marine biology and contributions to the conservation movement. She doubtlessly had a deep love of nature and the earth, inspiring multiple eco-feminist scholars as they examined overlaps between sexism and environmental damage. In her personal life, Carson shared an intimate relationship with Dorothy Freeman. The two exchanged a trove of letters, many of which were burned, arguably based on the assumption that they would be understood as "lesbian" in nature. Since we lack access to the burned letters, it is difficult to conclusively categorize Carson's sexuality, but many queer historians and biographers note that categorization of her sexuality is not necessary. Her love for Dorothy Freeman, regardless of contemporary understandings of sexuality, was an important aspect of her life, and the letters that survive are both beautifully written and show the deep bond the two women had.

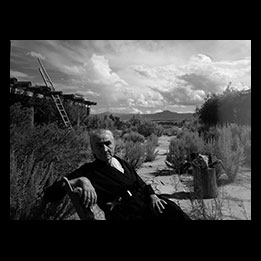

Arnold Newman, photographer, Georgia O'Keeffe at home, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, August 2, 1968.

Arnold Newman Papers and Photography Collection 5233O'Keeffe's relationship with women and the subject matter of her most famous paintings sparks fierce debate amongst biographers and art historians. She had a close friendship with Maria Chabot, a queer woman with whom O'Keeffe exchanged hundreds of letters. Furthermore, her famous flower paintings have been controversially described as yonic, an assertion O'Keeffe disliked due to the Freudian readings of women's sexuality male critics superimposed onto her work. While male art dealers and critics frequently commented on her floral paintings as "vaginas" in gauche, sexualized terms, queer women have long admired and identified with her work. Other queer authors (such as Virginia Woolf and Amy Lowell) have used flowers to symbolize intimacy between people with vaginas, and artist Judy Chicago based her iconic work, "The Dinner Party," on O'Keeffe's iconic flowers.

Una Troubridge, Diary excerpt, June 21, 1943.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 32.4Here we have an excerpt from Troubridge's diary. While most commonly known for her association with Hall, Troubridge had significant relationships with many people in her life.

Kay Dick, Article on Stevie Smith, manuscript, 1971.

Kay Dick Collection 14.10Smith lived the majority of her life without sexual or romantic partners. She and her work have been interpreted as lesbian, bisexual, and asexual. However, while Smith never made conclusive statements about her sexuality, she was adamant that the personal fulfillment she felt from her intimate relationships with friends and family matched any that she might have received from romantic partners. For many asexual theorists and fans of her work, her emphasis on the importance of emotional attachment outside of sex and romance resonates. Similarly, her poems featured cartoons with ambiguously-gendered bodies.

Smith is known for her wit and dark humor, and fans of her work included author Sylvia Plath.

Bi and Ace Erasure

Queer historians and literary scholars have deliberately and systematically erased the bisexual identities of countless authors. A great many bisexual authors had deep, fulfilling relationships with people of a range of genders. For Una Troubridge, while her relationship with Radclyffe Hall dominated her life, she still expressed at least some romantic and sexual attraction to men. However, there is also a problem of categorization. Certainly plenty of people married and entered relationships with people of other genders despite a lack of romantic or sexual attraction due to social pressures or needing some protection from legal consequences of non-conformity when it came to gender presentation and sexuality.

Similarly, many asexual and aromantic authors, artists, and thinkers lived deep, rich, emotionally-fulfilling lives without feeling the need for sexual or romantic partners. Both acephobia and biphobia, cultural allegiance to monosexuality (attraction to one gender), and trans-erasing insistence on gender binaries have deep and problematic roots in even lesbian and gay-specific spaces and scholarship.

For educators, these documents offer a chance to think critically about bisexual and asexual identities and how their relationships with people of different genders have been minimized or erased or mischaracterized. For students, these documents offer a chance to "dig in" to complicated questions about gender and sexuality as a spectrum that is not always easily defined by simple categories. For everyone, it highlights and celebrates the bi identities of different authors whose writings offer a rich trove of resources for bisexual/pansexual and asexual scholarship.

Unidentified maker, Jacket owned by Carson McCullers, circa 1950s.

Carson McCullers Collection 5.47Famous for her pioneering work in the southern gothic genre, Carson McCullers remains a captivating focus for queer disability scholars. McCullers, who spoke relatively openly with her friends about her attraction to multiple genders, is remembered also for her flamboyant wardrobe and sense of style. Though her childhood in Georgia provided significant inspiration for her creative work, she spent much of her adult life as a member of queer-dominated literary scenes in New York. Friends included fellow queer southerners Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote.

Disability frequently appears in her work, and McCullers lived with chronic illnesses (both physical and mental) for much of her life. Ability, like sexuality, served as a marker of difference in her works, and she relied closely on her experiences as a bisexual, disabled woman to craft her well-defined characters.

Djuna Barnes, Letter to Charles Henri Ford, July 25, 1935.

Charles Henri Ford Papers 12.3Known to have had romantic and sexual relationships with multiple genders, Barnes published her own landmark work of queer literature, Nightwood (1933). Barnes influenced a range of authors, including Carson McCullers and Shirley Jackson, and became an emblem of Greenwich Village's literary scene in the mid-twentieth century. A known globe-trotter and sophisticated fashion icon in her own right, she spent time in multiple cities that would be influential on Hall and Troubridge, including Paris and London.

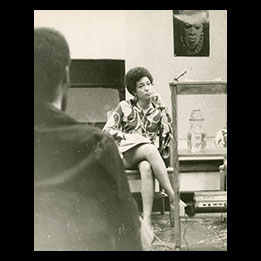

Lloyd Yearwood, photographer, June Jordan, circa 1970.

National Museum of African American History and Culture 2014.150.8.37The bisexual poet June Jordan lived unapologetically as a queer Black woman of Caribbean heritage. Passionate in her support of Black feminism and specific in her critique of white-dominant conversations about discourse and sexuality, Jordan insisted on writing in what she called "Black English" as a radical break from "Standard English," which she regarded as overly White and saturated with racism. Jordan saw bisexuality as liberatory and a natural extension of humans as complex beings. Bisexuality, she believed, was innately difficult to control and was, therefore, an act of rebellion against authoritarianism. Dedicated to human equality, Jordan wrote against apartheid practices and brutality in Ireland, South Africa, and Palestine in addition to challenging racism in the United States.

United Press International, photographers, Tallulah Bankhead with Tennessee Williams, undated.

Tennessee Williams Literary File Photography Collection P-437Alabama-born actress Tallulah Bankhead spoke relatively openly about taboo subjects of sexuality. Politically and socially outspoken, she referred to herself as "ambisextrous," and had romantic and sexual relationships with people of multiple genders in her life. She lived through several prominent changes in how American culture understood human sexuality, including the publication of the 1948 and 1953 Kinsey Reports. She, like many stars of the Classic Hollywood era, garnered a significant queer fanbase, and she remains something of a "gay icon" with enduring popularity in a range of queer cultural spaces, such as drag shows and movie clubs.

Bankhead is pictured here with her friend, the prolifically southern and prolifically queer Tennessee Williams.

Edward Gorey, Untitled drawing, circa 1950.

Edward Gorey Art Collection 2002-7Identifying as both gay and asexual in interviews, Edward Gorey crafted what he considered an asexual universe in his morbid, darkly comedic artwork and stories. Focusing on Victorian and Gothic themes, Gorey frequently bristled at art and literary critics who attempted to superimpose sexualized meanings on his works.

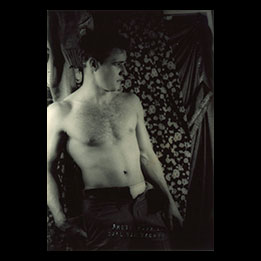

Carl Van Vechten, photographer, Marlon Brando, December 27, 1948.

Theater Biography Collection 56Marlon Brando, like Bankhead, has a queer fan base that transcends gender. Photographed here in a publicity shot for A Streetcar Named Desire, Brando's good looks and prodigious talent as an actor make him an enduring icon of a shift in acting techniques towards "method" rather than "technical performance." Politically outspoken, Brando mentioned in interviews that he'd had sexual experiences with men, and he was rumored to have had relationships with Richard Pryor and James Baldwin (Brando's former roommate).

Story Telling: The Role of Partners and the Ghosts of Authors

While not every queer author wrote about death, death proved just as complex and uniquely challenging for them as life did. Laws and norms that did not legally recognize same-gender partners as legal heirs made inheritance and creative control difficult to navigate. Similarly, defining legacies and the need to protect the privacy of living partners duplicated the need for discretion for authors who passed away.

For contemporary queer authors, the HIV/AIDS crisis casts a long shadow. With many queer people dying at alarming rates from AIDS-related illnesses, many same-gender partners and transgender partners who lived with them for years suddenly found themselves with little legal right to shared property and in many cases were not allowed to visit their loved ones in hospitals in their final days.

The more painful aspects of personal life and the difficulties of any partnership also influenced the role that surviving partners and estates played in organizing and publishing posthumous works of authors. This subcategory examines what role partners play in posthumous guardianship of their partners' estate, papers, and reputation. Here we examine how Troubridge, like many others publishing biographies of authors and seeking to control the narrative of their deceased loved ones, omitted facts and deliberately destroyed letters that reminded her of painful parts of her marriage to Sir Ernest Charles Thomas Troubridge, and of her partnership with Radclyffe Hall. However, the material records of that writing process also served as a testament to the deep belief many partners held about the greatness of their deceased loved ones. Similarly, this category also examines the role that the queer rights and women's rights movements played in critical re-evaluation of authors who died prior to those political movements in the late 20th century.

How did feminist politics and queer liberation impact the work of dead authors? How do their surviving partners fit into their narratives not just as executors of estates, but also of authorship and publication? How do queer archivists position partners as equals in relationships instead of falling into sexist, partiarchal tropes that relegate spouses to "supporting" roles or shadows in the background?

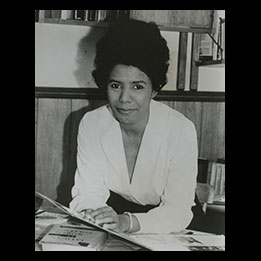

Unidentified photographer, Lorraine Hansberry, 1973.

Theater Biography Collection 742A closeted lesbian, Hansberry and her politics marked stark contrast to many other queer writers during her lifetime. Isolated already as a leftist sympathizer and needing to delicately balance personal beliefs with financial security, Hansberry took incredible risks by offering political support to the early LGBTQIA+ rights movement in the US, including publishing works in lesbian magazines. Astute in her political understanding of the world and commercially successful as a Black woman playwright, Hansberry won critical acclaim and lasting admiration for her creative work and her advocacy for social justice. She offered more open support for lesbian rights movements in her later years. However, when her ex-husband donated her papers after her death, he did so with the condition that any contents that might identify Hansberry as a lesbian not be made publicly available. While queer-of-color scholars and Black-feminist scholars only recently began examining these valuable papers that attest to Hansberry's experience as a Black lesbian, Hansberry's life doubtlessly influenced her work that earned her a place of distinction as one of the great American playwrights. However, her life and experience as a lesbian Black woman offers new lines of inquiry into her creative work and political life.

Lillian Hellman, Janet Flanner tribute, manuscript, 1978-1979.

Lillian Hellman Papers 61.3Playwright Lillian Hellman offers an obituary for the journalist Janet Flanner. A lesbian for much of her adult life, Flanner was a fixture of the American literary scene in Paris for five decades. She maintained close connections to other queer women, including Getrude Stein, Alice Toklas, Sylvia Beach, and her own partner, Solita Solano.

Hellman's obituary, coming at the height of the 1970s Women's Liberation movement, specifically takes up Flanner's role as a pioneering woman journalist and trailblazer for women in her line of work. Her biography also includes coded nods to Flanner's identity as a lesbian, such as her admiration of her "finely tailored suits."

Bryher, Letter to Marianne Moore, June 24, 1950.

Marianne Moore Collection 1.10Bisexual poet Hilda Doolittle (known as H.D.) and writer/editor Bryher (pen name for Annie Winifred Ellerman) lived together for a time and were romantic partners and literary collaborators for much of their lives. H.D. represents the significance of the rise in feminist academic discourse that gave new fame and prominence to women authors who specifically wrote about women's lives and experiences.

Bryher, a lesbian, was also a noted magazine editor, writer and critic.

Una Troubridge, Diary excerpt, June 21, 1943.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 32.4Hall's romantic relationship with Evgenia Souline deeply hurt Una Troubridge. Upon Hall's death, Troubridge quite literally did everything in her power to erase Souline from Hall's legacy. She destroyed their letters and largely ignored her presence in Hall's life when she began constructing Hall's biography. Whatever intimacies Hall and Souline expressed for each other in writing are for the most part lost. However, this inclusion is important for several reasons. Primarily, it shows modern readers that queer relationships are not without complications and difficulties. The pain Troubridge felt was real, though not enough to deter Hall's attraction to Souline. It also demonstrates that narratives controlled by partners are not, of course, objective. However, questions about the necessity of objectivity also emerge from this. Is any biography truly objective? What does Troubridge's dual role as romantic partner and executor of a literary estate tell us about the importance of surviving partners and their control over legacy?

Willa Cather, Letter to Edith Lewis, October 4, 1936.

Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial Collection 1328Edith Lewis outlived her partner Willa Cather by almost three decades. After 40 years of living together, the grief that she felt must have been extreme. Like Troubridge, who tailored Hall's suits and wore them herself as she constructed a biography of her late partner, Lewis dedicated her time to memorializing Cather. Cather, one of a handful of women to win a Pulitzer Prize in literature, had somewhat fallen out of favor in her later years as literary interests about the plains focused more directly on questions of class and adopted a more overt leftist political lens.

Lewis, an editor by training, provided Cather with feedback and advice when it came to her creative work, and when Cather died in 1947, Lewis began working to memorialize her late partner in the 1953 biography Willa Cather Living.

Emily Dickinson, Poems (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1890).

Houghton Library AC85.D5605.890p (B)Contrary to popular mythology that Dickinson did not want her work published, she bristled not at the thought of publication, but at male editors changing her meter, punctuation, and capitalization. When she died, her sister Lavinia followed her instructions and destroyed her letters and personal correspondence. However, publishing her poetry after death proved challenging and controversial. While her sister-in-law, close friend, and speculated romantic partner Susan Huntington Gilbert initially assumed some role in preparing Dickinson's works for publication, she did so too slowly, and the work shifted to Mabel Loomis Todd, a woman with whom Susan's husband had an extramarital affair, much to Dickinson's fury. Todd, partnering with T. W. Higginson, published early collections of Dickinson's work, notably editing her punctuations and other stylistic choices, and removing dedications to Susan Gilbert Dickinson from several of her poems.

This inclusion is notable in several senses. First, the destruction of personal papers leaves a gap that Dickinson deliberately created by ordering her papers burned. Her sister Lavinia, dedicated to ensuring Dickinson's legacy as a great American poet, balanced personal guardianship over her legacy, but also wanted her works broadly published. Susan Gilbert Dickinson's role as trusted friend of Dickinson's and her erasure from the first published collection also provides intrigue for queer scholars who have viewed the relationship between Dickinson and Gilbert with particular fascination. While publishers did eventually publish anthologies of Dickinson's work as she wrote it, editing her style and omissions of dedications clouded the first collected publication.

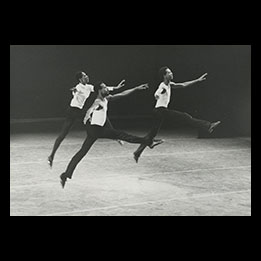

Fred Fehl, photographer, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater production photographs of Toccata, 1969.

Fred Fehl Dance Collection 1.14Black dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey was pioneering in his use of multiple forms of dance and focused his many of his works specifically on the experiences of Black Americans. At the height of the crisis, Ailey died from AIDS-related complications, a diagnosis that was intentionally hidden due to intense stigma that those who died of the virus faced. Similarly, Ailey guarded his private life extremely closely. Discourse of "the closet" is not particularly meaningful and assumes a singular goal of "outness" that not all queer people shared. His decision to keep his romantic life private, whether out of a desire for privacy or a sense of professional preservation, extended beyond his death.

However, this artifact illustrates the momentous task of handling the legacies of the HIV/AIDS crisis, and centering the grief and loss of considerable artistic talent. Government neglect and an inadequate healthcare system needlessly cost countless people their lives. For queer communities (especially queer men and trans women) the collossal loss of life and culture cannot be overstated. When thinking about queer legacies, HIV/AIDS is an unavoidable topic. Though HIV/AIDS did not appear until several decades after Hall's death, the question of legacy and remembering queer contributions to art, science, athletics, and literature runs throughout the twentieth century.

This question is especially poignant when it comes to queer-of-color critiques. While Hall certainly faced discrimination based on homophobia and misogyny, she did not have to worry about racism or classism when it came to her access to space or when it came time to euologize her. Stigma against queer people of color, even in death, crafts a bitter question for queer-of-color scholars. What lives do people view as "grievable?" How must queer-of-color critique take up questions of legacy in ways that are distinct from White queer scholarship?

W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, The Entertainment of the Senses, manuscript, undated.

W. H. Auden Collection 1.1Auden and Kallman had a relationship that fluctuated between deep friendship, creative collaborator, and sexual partner. Here we see one of the many collaborations they made together over the course of their partnership.

Upon his death, Auden left his estate to Kallman.

Takedown Notice: This material is made available for education and research purposes. The Harry Ransom Center does not own the rights for these items; it cannot grant or deny permission to use this material. Copyright law protects unpublished as well as published materials. Rights holders for these materials may be listed in the WATCH file. It is your responsibility to determine the rights status and secure whatever permission may be needed for the use of any item. Due to the nature of archival collections, rights information may be incomplete or out of date. We welcome updates or corrections. Upon request, we'll remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. The unpublished works, correspondence, diaries, and daybooks of Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge are under copyright in the United States. The Ransom Center is grateful to Alessandro Rossi Lemeni Makedon, the representative of Troubridge's estate, who has granted permission for the Center to share the papers of Troubridge.