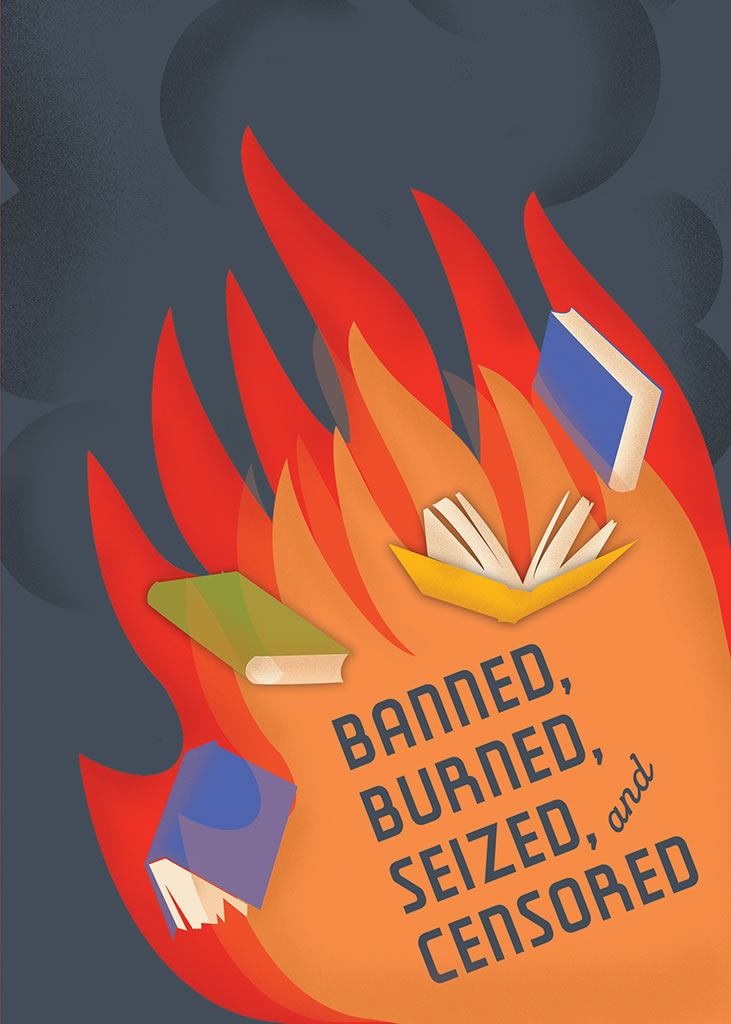

Banned, Burned, Seized, and Censored

September 6, 2011 – January 22, 2012

"I read with infinite pleasure your brilliant novel... but I could not think of publishing it as a book—life is too short and the jails are unsanitary."

—Liveright, Inc. to Parker Tyler, June 30, 1932

The exhibition Banned, Burned, Seized, and Censored reveals the machinery of censorship at work in America during the interwar years, letting writers, reformers, attorneys, and publishers speak for themselves and illuminating the complex negotiations that occurred at the intersection of literature and "obscenity."

In November 1935, John Saxton Sumner presided over the New York City Police Department's annual burning of obscene literature. Over $150,000 worth of magazines, books, pamphlets, and postcards confiscated from publishers and booksellers went into the furnace, transforming them, as one newspaper noted, "from filth to smoke." Sumner, Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, had become one of the most recognizable figures in a nationwide effort to rid the country of offensive literature, and the book burning was just one manifestation of this vast, multifaceted movement.

Sumner and his vice society agents raided New York City bookshops and publishing houses, confiscating books and prosecuting writers, booksellers, and publishers in courts of law. In Boston, "objectionable" titles quietly disappeared from bookstore shelves and newsstands at the behest of a committee of booksellers operating under the auspices of the Watch and Ward Society. Customs agents seized books at the borders, and postal inspectors confiscated materials from the mail. Before agreeing to select books for inclusion in their catalog, Book-of-the-Month Club reviewers asked writers and editors to excise passages that their readers might find offensive.

For more than 20 years, the battle over obscenity in literature captured the popular imagination and filled the pages of newspapers and magazines. Photographers snapped Upton Sinclair wearing a fig-leaf sandwich board as he sold his banned novel Oil! on the streets of Boston. Reporters followed the landmark 1933 trial of James Joyce's Ulysses, a case initiated very intentionally when defense attorneys notified the customs bureau precisely where and when to expect the arrival of the book. Critics of the "smuthounds" decried the suppression of artistic freedom in editorial after editorial.

John Steinbeck, Radclyffe Hall, Richard Wright, Henry Miller, and a host of other writers came under fire for their exploration of themes and use of language deemed inappropriate by would-be censors. The literary merit of classics such as Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron was debated alongside new works like D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover. Across the country, writers and publishers struggled to balance artistic integrity with a desire for sales and a real fear of time in prison. Some American writers sought European publishers for their work; others fled the United States altogether.

By the onset of World War II, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, the New England Watch and Ward Society, the Postal Department, the Treasury Department, and even the Book-of-the-Month Club had irrevocably altered the American cultural landscape.