International Human Rights

Writers and Free Speech

Writers in Exile / Global

Refugees

Writing the Cold War

Writing World War II

Digital Collections

Writing the Cold War

Origins of the Cold War Strategy for Non-Political Activism

As an organization initially founded as a social society to foster free expression for a select literary

community, PEN eventually found itself committed to protecting the rights of a global community of writers. As

their mission evolved, PEN founders believed that they could intervene on behalf of writers in the midst of

some of the most contentious and controversial events, such as decolonization, and world war and its political

and social aftermath—without identifying itself as a political organization. PEN's identity as a human rights

organization changed over time, as the political climate changed and as writers around the world required more

protection and specific kinds of diplomatic intervention.

View Item

Letter from Hermon Ould to Noel Streatfeild regarding request to speak at PEN dinner. December 19,

1938.

PEN Records 67.5

View Item

Letter from Noel Streatfeild to Hermon Ould, "PEN is synonymous with no politics." June 23, 1939.

PEN Records 67.5

View Item

Letter from Noel Streatfeild to Hermon Ould with enclosure from the Spanish Writers Relief Committee.

June 16, 1939.

PEN Records 67.5

Sites of Struggle – PEN Geographies

Cold War struggles arose in many different places around the world, at times as a contest between

superpowers, and at other times as a clash between cultures or political ideologies. In the years following

World War II, PEN tried to intervene in places that were already historically marked by processes such as

decolonization. Nations such as South Africa, Cuba, and Vietnam faced a unique set of social and political

challenges resulting from the remnants of their relationships with imperial powers. In many places PEN worked

to ensure a forum for writers' voices and their free expression amid the residues of racial hierarchy and

political corruption left behind after the war.

For example, PEN International Secretary Hermon Ould worked tirelessly, with other members, to place a PEN

centre in South Africa. As envisioned, this centre would acknowledge the contribution of South African

writers, and would serve to counter the idea that all literature that emerged from the region centered on

themes of colonization. But while the centre was praised as a unique accomplishment among PEN members, it did

not renounce the structures of racial hierarchy and apartheid which divided the country and its literature.

South Africa

These materials document PEN's recognition of the need for a centre in South Africa, but they also reveal

some of the tensions present in its negotiations with existing political conditions in the country. By the

time of the Cold War, PEN began taking small steps to address societal inequalities, soliciting book donations

for students who had been excluded from opportunities due to gross inequalities inherent in a system of racial

apartheid. In the PEN News call for book donations, the author includes the language that would have

been used at the time, and refers to "non-white" school children, as PEN makes an effort to address

inequality. However, by encouraging the founding of a centre in the Afrikaans language—a language with an

exclusionary and hegemonic history—and by failing to acknowledge black writers for the first two decades of

the South African Centre's existence, PEN missed an opportunity to use its influence on behalf of a wider

range of African literatures, or to use its platform to discourage apartheid. These materials open up

discussions regarding how PEN's presence could both signal change and simultaneously maintain a status quo.

Students might ask, for example, what it means for an international organization to focus first and foremost

on literature in the languages of colonial powers.

View Item

Letter from Dorothea Fairbridge to John Galsworthy. June 21, 1927.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

Letter from the Acting Secretary of London PEN to Mrs. Percy Leake. Circa 1925.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

Letter from Hermon Ould to Lily Tobias. February 22, 1944.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

Letter from Hermon Ould to Eric Rosenthal. August 14, 1945.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

"The South African Book World: A Book Exhibition at South Africa House," clipping from South

Africa. July 27, 1946.

PEN Records 79.10

View Item

"S.A. Author Analyses Hofmeyr's Ideals," press clipping from Natal Mercury, Durban, South

Africa. January 25, 1949.

PEN Records 79.10

View Item

"Books for South African Non-White Schools," announcement in PEN News, No. 201. Autumn 1962.

PN 121 P22

Cuba

The effort to place a PEN centre in Cuba continued for decades and finally came to fruition in 1945. Some of

the correspondence in the collection reveals a fascination with the people and the place. PEN International

President Arthur Miller even acknowledged that holding a PEN congress in Cuba would satisfy an American

curiosity about what "goes on over there," situating Cuba as both a site of contention as a potential USSR

satellite, but also as a geographical and racial "other."

View Item

Letter from Arthur Miller to David Carver. November 24, 1967.

PEN Records 154.2

View Item

"Campaign on Cuba: Recommended Actions," a handout from the PEN International Writers in Prison

Committee. June 1997.

PEN Records 243.3

View Item

"Dangerous Writers": Freedom of Expression in Cuba, a report from the PEN International Writers in

Prison Committee. May 1997.

PEN Records 243.3

Vietnam

In the late 1960s and 1970s, at the height of the Vietnam War, known by the Vietnamese as the American War,

PEN International President Arthur Miller and PEN International Secretary David Carver tried to protect

writers, prevent persecution, and publicly protest abuses. They struggled to calibrate their intervention into

international affairs of state, understanding PEN's mission as an apolitical rights group but participating in

overtly political conditions.

View Item

Letter from Nghiêm Xuân Thiện to David Carver. March 16, 1968.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

"South Vietnam Bloody New Year," a newsletter by Nghiêm Xuân Thiện. 1968.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

First-hand account by unidentified author for The Deer Hunter research. January 24, 1966.

Robert DeNiro Papers Box 45.3

View Item

The Nine Dragons Hymn: Ten Poems from Vietnam with Original Texts in Vietnamese, by Nghiêm

Xuân Việt. 1966.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

Letter from David Carver to Vũ Hoàng Chương. May 4, 1966.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

Telegram from David Carver to Nguyễn Ngọc Thơ, Prime Minister of South Vietnam. November 4, 1963.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

Declaration from the PEN Vietnam Centre. December 30, 1965.

PEN Records 154.4

View Item

"Notes on Authorship in Vietnam," by Bernard Newman. June 24, 1953.

PEN Records 154.4

PEN Middle East Pre-war and Post-war Efforts

View Item

PEN Dinner Menu, Cairo, Egypt. February 27, 1935.

PEN Records 77.5

View Item

"Jerusalem as a Congress City," advertisement by Y. Rischin, reprinted from Israel Economist

Annual, 1951.

PEN Records 78.8

View Item

"Jerusalem Convention Centre: New Venue for World Conferences, Festivals, and

Exhibitions," brochure by Alexander Ezer, reprinted from Israel & Middle East, No. 6-7.

December 1950.

PEN Records 78.8

PEN Contesting Global Dominance: U.S. vs. USSR-centered Conflict

View Item

Letter from Arthur Miller to David Carver. October 22, 1967.

PEN Records 154.2

View Item

"Arthur Miller Tangles with LBJ," newspaper clipping from The Guardian. September 28, 1965.

PEN Records 154.2

View Item

Mike Wallace Interview with Henry Kissinger. July 13, 1958.

Mike Wallace Interview Collection HRC_WAL0036

View Item

The Atomic Submarine, movie poster. 1959.

Interstate Theater Circuit Collection 01334

View Item

Report on the 24th International Congress, Nice, France: Monday, June 16th, Morning Session,

reprinted in PEN News, No. 181. November 1952.

PN 121 P22

View Item

"Who is hindering contact between writers?," report by the Soviet Writers Union in Literaturnaya

Gazeta. July 28, 1966.

PEN Records 154.1

PEN and Commercial Pressures

By the 1950s PEN, like the rest of the country, was faced with the conundrum of peace versus prosperity. The

"booming" American economy introduced both new possibilities and new kinds of commercial, consumer, and

cultural pressures. As more American families were pushed to consume and more employee productivity was

measured, and technologies like television became pervasive, some Americans began to contemplate the morality

of mass consumption. For an organization like PEN, historically wedded to a certain set of literary standards,

the idea of mass consumption, and the concept of the commercially successful writer forced PEN to contend with

a high-culture versus low-culture dilemma. Is commercially successful writing still considered literature? How

does PEN struggle to remain relevant to and for writers at this time of economic upheaval and social change?

View Item

"Screenplay and Literature," lecture reprinted in PEN News, No. 155. May 1948.

PN 121 P22

View Item

"Writing for television," advertisement in PEN News, No. 199. Autumn 1960.

PN 121 P22

View Item

Executive Suite, movie poster. 1954.

Interstate Theater Circuit Collection 01286

View Item

"BBC Notes on Radio Drama," a guide from the British Broadcasting Corporation. 1970.

PEN Records 205.3

PEN and the Prospect of Global Citizenship: Are Writers Bound by Nation or Language?

We can learn about PEN's trajectory as a human rights organization by looking not only at the places in which

it chose to intervene, but also at the places it did not. Countries such as Vietnam and the USSR serve as

logical places of inquiry, but what can we determine about places that PEN did not represent or in which it

did not open centres? Even when PEN did choose to locate a centre in a geographic location, how did PEN work

around social and political restrictions such as racial hierarchy in South Africa, or political and class

division in Southeast Asia? While PEN was actively defending the rights of writers around the world, it was

also complicit in a set of global politics which determined what qualifies as literature. Their decision to

open a centre in South Africa recognizes a certain kind of literary diversity, but it also priveleges European

concepts of literature, which include a particular set of ideas and literary conventions, while simultaneously

excluding other writers on the basis of race, gender, or nationality. The following examples demonstrate that

at certain historical moments PEN privileged a particular type of national literature – only Afrikaans

in South Africa – or ignored literature from places such as Cambodia and Laos.

View Item

Speech delivered by Hermon Ould at the 23rd International Congress, reprinted in PEN News, No.

177. October 1951.

PN 121 P22

View Item

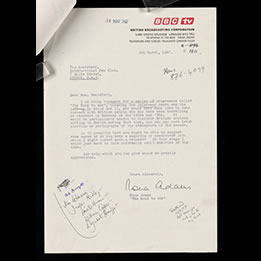

Letter from Mona Adams to PEN International Secretary. March 9, 1987.

PEN Records 205.3

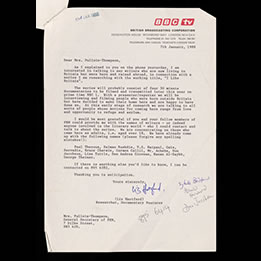

View Item

Letter from Liz Hartford to Josephine Pullein-Thompson. January 7, 1988.

PEN Records 205.3

What Does It Mean to Claim a National Literature?

View Item

Opening Statement by Lily Tobias for a meeting of the South African PEN Club

at the Carleton Hotel in Johannesburg, South Africa. February 28, 1945.

PEN Records 54.2

View Item

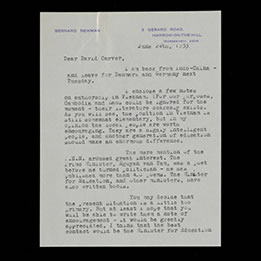

Letter from Bernard Newman to David Carver. June 24, 1953.

PEN Records 154.4

We have attempted to minimize harm or adverse impact by selecting primary sources

that we believe will not place people at risk. Please notify us at reference@hrc.utexas.edu if you believe we need to remove any

materials from this digital collection.

Takedown Notice: This material is made available for education and research

purposes. The Harry Ransom Center does not own the rights for these items; it cannot grant or deny permission

to use this material. Copyright law protects unpublished as well as published materials. Rights holders for

these materials may be listed in the WATCH

file. It is your responsibility to determine the rights status and secure whatever permission may be

needed for the use of any item. Due to the nature of archival collections, rights information may be

incomplete or out of date. We welcome updates or corrections. Upon request, we'll remove material from public

view while we address a rights issue.