Hall-Troubridge Teaching Guides

These guides have been developed to provide resources to instructors interested in teaching with the Hall-Troubridge Digital Collection and to offer students the opportunity to engage with archival resources to enrich their learning experience.

Indecent Behavior: Sexuality, Gender, and Transgression

Human sexuality and gender identity have long been a point of fixation for law-making cultures. Contrary to a linear understanding of progress, sexuality and gender both have rich, complex, and shifting relationships with the law. One of the largest influences on sexuality and gender laws on a global scale remains British colonization. At the height of imperial expansion, the British government codified anti-LGBTQIA+ laws and policies across the planet. While some countries never saw the need to make laws about certain sexual acts, others began the process of either legalizing or criminalizing same-sex sexual acts at different points in history. While many countries officially legalized same-sex activity in the mid-20th century, others, such as France, legalized it in the late-18th century, a time period in which laws in the United Kingdom and the American colonies specifically deemed male same-sex activity a capital offense. The death penalty on the basis of "sodomy" remained on the books in the United Kingdom until 1861, with the last known execution taking place in 1835, less than 100 years before Hall would pen The Well of Loneliness. The impacts of such laws on societies remain. In the US and the UK, laws designed to prohibit "lewdness" and to eliminate "vice" resulted in stringent regulations banning the mailing, selling, or distributing of "obscene" materials. In the United States, the infamous Comstock Act of 1873 regulated definitions of "obscenity." Using the nebulous "Hicklin Rule'' from British obscenity laws, "indecency" became defined by whether a book or sections from it could have a "corrupting" influence on the minds of susceptible readers. Hall became intimately familiar with the legal arguments and challenges in various attempts to allow publication of The Well of Loneliness to English-speaking audiences. Furthermore, Hall felt strongly about her obligation to defend The Well of Loneliness on specific arguments that did not discount the book or its contents. Believing the work to be culturally significant, Hall insisted that the book and the characters in it be discussed candidly and not mischaracterized for the sake of legal expediency.

Hall was certainly not alone. Countless people found themselves on trial for "obscene" actions that were perceived to violate the norms of sexuality and gender identity. In fact, for LGBTQIA+ archivists, "obscenity" becomes a grimly useful tool for finding queer material in historical papers that might not have used contemporary terms for same-sex acts. Transgressions of unjust laws placed many queer people in archives, particularly when it came to publishing books, nonfiction, and art or for simply engaging in community-building or participating in romantic and sexual relationships. "What is obscenity? What is literature? What is the difference between the subject & the treatment?" Virginia Woolf puzzled in her diary when the British obscenity trial of The Well of Loneliness began in November of 1928 (Parkes 145). Hall anticipated that the book would be sensational and polarizing, letting her publisher, Jonathan Cape, know that the book would require an act of faith. While the book was certainly not the first to include lesbian themes, what made Hall's novel distinguished was the manner in which it positioned the lesbian protagonist, Stephen Gordon, as noble, likeable, and sympathetic. Lesbian themes were broadly ignored in Victorian culture. Same-sex relationships and sex acts between women were never explicitly banned or even addressed in British law. However, the novel's publication was met with polarized opinions. While the intelligentsia of British literature supported the book's publication on liberal beliefs in free speech, most privately found the book unimpressive in terms of craft. However, many individuals wrote to Hall about how important and meaningful the book was for them when it came to depicting lesbians unambiguously and in a manner designed to elicit sympathy and tolerance rather than mockery and condemnation. Other commentators, particularly social conservatives who saw the book as another aspect of the amoralism of modernism, were particularly acidic in their panning of the text.

James Douglas, a conservative journalist for The Sunday Express, led a highly sensationalized charge against the book, claiming it would corrupt children and arguing that the book was anti-Christian. Rather than provide a commentary on the book's merit as literature, the subsequent media frenzy exposed long-simmering public divides. Connecting queerness with German and French decadence, Douglas astutely tapped into lingering British anti-continental sentiment and held the text up as an exemplar of the havoc that social liberalism could potentially wreak on war-weary British readers. Left-leaning organizations, academics, and social advocates (to whom Hall was not politically sympathetic) sided with Hall, attacking Douglas's reputation as a media sensationalist and conservative fear-monger.

Within only a few months of its publication in 1928, the book was on trial for obscenity. Numerous witnesses expected to be sympathetic were contacted, including both Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Vita Sackville-West, Havelock Ellis, and other experts in literature and sexual psychology. However, the response was lukewarm. Many potential witnesses refused to reply. Others offered tepid excuses for why they could not participate. Even sympathetic parties (such as the Woolfs) prepared to take the stand with extreme misgivings. The book, most British modernists felt, was old-fashioned, unimaginative, and polemic. Skeptical of Hall's work as an artist, they prepared to defend the book on the grounds of free speech, but secretly felt that the book was more trouble than it was worth. Woolf, for her part, published Orlando the same year. Saturated with queer themes, Woolf's fictionalized biography of her romantic partner Vita Sackville-West, mocks rigid categorizations of gender and sexuality and uses fantasy as a method for insulating the book against the public criticism that Hall's Victorian prose faced.

Ultimately, their presence as witnesses proved unnecessary. The magistrate Sir Chartres Biron deemed that only he and not a line of witnesses could determine if the book was obscene. He ultimately ruled against The Well of Loneliness, under the Hicklin Rule interpretation of obscenity. His categorization of the text as obscene was upheld on appeal. The Well of Loneliness fared better in the United States, where the text prevailed in court against similar obscenity charges. Jonathan Cape, much to Hall's annoyance, ceased publication in the UK, handing printing of the book off to the Paris-based Pegasus Press.

This section specifically examines primary sources related to The Well of Loneliness trial. Instructors might use this section to set the trial within historical contexts of the time. Similarly, this section somewhat challenges the cut-and-dry approach to liberal anti-censorship discourse. Hall did not want the book defended on the basis of freedom of speech, nor did she want to dismantle public understandings of obscenity. These documents reveal the nuances and complexities of a trial that went against the author's wishes in numerous ways. Students might ask themselves if artistic merit is an important consideration in how a book is defended. Furthermore, the divide is worth considering between the intelligentsia (who were more interested in modernist styles of writing and themes) and those in the public who privately treasured The Well of Loneliness for discussing lesbianism in ways that felt familiar to them.

Unidentified compiler, Banning of The Well of Loneliness, scrapbook, 1928.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 24.3These six pages reflect Hall's scrapbooking of articles relating to The Well of Loneliness and its publication. They show the stark public divide in reception to Hall's depiction of same-sex desire and lesbian identity. However, they also reveal how the book simply became a lightning-rod for broader cultural anxieties and social divisions in the post-World War I period.

Rubinstein, Nash & Co., Scotland Yard and The Well of Loneliness, April 1929.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 17.5This excerpt from a typescript tracing the suppression of The Well of Loneliness in the UK summarizes Hall's challenges with the text's publication. Small edits run throughout the pages, such as the replacing of "England" with "Scotland Yard" and the deletion of "Miss" in front of Hall's name.

Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst, The People of the State of New York vs. Donald Friede and Covici-Friede, Inc., 1929.

Morris Leopold Ernst Papers 235.4Jonathan Cape sold the American publication rights to Pascal Covici and Donald Friede, who, in turn, enlisted Morris Ernst (general counsel of the American Civil Liberties Union) to defend the book against obscenity charges in the US. The document shows the defendants' legal argument: that the book is culturally and artistically significant and that there are precedents against censorship of such books in American courts.

Radclyffe Hall, Letter to Havelock Ellis, June 4, 1928.

Havelock Ellis Collection 17.6Though Havelock Ellis wrote the foreword to The Well of Loneliness and was an important figure in the Sexology field that Hall used extensively to categorize Stephen Gordon as an "invert," Ellis kept the book at arm's length when it went to trial, refusing to serve as a witness. Though it was ultimately a moot point, Hall was likewise unable to rise to the book's defense during the obscenity trial. Since the legal argument was that the book was sincere, Hall's testimony was not deemed necessary, as the book was testimony of the author's views in and of itself.

Furthermore, for Ellis, the campaign against The Well also was an effort by cultural conservatives to call into question the scientific merit of sexology, who labeled it, among other things, a quack science.

Radclyffe Hall, Letter to Mr. Murphy regarding The Well of Loneliness court case, undated.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 17.3Hall writes a letter here to preface documents and letters about the trial.

Pegasus Press, Statement concerning republication of The Well of Loneliness, 1928.

Radclyffe Hall and Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge Papers 17.2Cape privately leased the publication rights of the book to the Paris-based Pegasus Press, who took advantage of enhanced publicity of the book to sell it prior to the obscenity trial.

Isaac S. Heller, Letter to Morris L. Ernst of Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst, June 6, 1929.

Morris Leopold Ernst Papers 234.5Writing to Ernst, Louisiana attorney Isaac Heller updates the defendants in New York about how he successfully defended the book against obscenity charges and prevented censorship of the book in New Orleans. In his argument, he clarifies that while the book's content might be "harmful" to some, it does not rise to the accusations of deliberate public ruin that would be necessary for the book to be labeled obscene under American law.

Long Arm of the Law

For many queer archivists and historians, interactions with the law are some of the only ways to find unambiguous records of queer sexuality. These records are, of course, deeply tenuous and troubling to navigate. On one hand, they compartmentalize queer people as "law-breakers" and assign labels in the present day to past private romantic and sexual relationships that many actively sought to keep concealed from public view. For queer historians, the decision to use and highlight legal transgressions in research can be a political one. It demonstrates a willingness to use the material remains of a deeply homophobic society to pinpoint public, humiliating, and often career-destroying moments for those caught unjustly in the grips of homophobic and transphobic legal systems. However, there is also a question of what any decision to not use such documents might mean for queer history. For many public historical figures, such moments are already well-known. As mentioned, they also offer historians concrete evidence, otherwise hard to discover, in a world of documents peppered with innuendo and deliberate omission. Educators and students using these materials can and should engage with the politics of using legal documents and legal transgression records when it comes to studying queer content. What do legal transgressions teach us about the nature of privacy and confidentiality? How do these records allow for speculation about why other queer people might have left much more discreet written records, or about the privileges of those who may have been more open? Is there a way to glean information from legal and medical documents and legal histories without adding even more public focus onto the implications of breaking unjust laws?

Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest (London: L. Smithers and Co., 1899).

Thomas Edward Hanley Library PR 5818 I4 1899 Copy 2Arguably his best-known work, The Importance of Being Earnest and its premiere occupy a conflicting time period in Oscar Wilde's life. As was the case in many European and North American countries at that time, sodomy was illegal in the United Kingdom in 1895 when the play opened. Wilde, romantically and sexually involved with Lord Alfred Douglas, misguidedly sued Douglas's father for libel when he began accusing Wilde of engaging in same-sex relationships. When Wilde's private letters proved the accusations against him to be true, he was jailed for gross indecency, all of which took place as The Importance of Being Earnest played to sold-out houses.

Remembered today for his gifts as a wordsmith and playwright, Wilde also casts light on the draconian impact of sexual morality laws that wreaked havoc on countless people. Many Victorian and Edwardian queer Britons likely enjoyed rich private lives that they navigated with caution. However, public trials such as Wilde's offer archivists and historians some of our only direct written examples of unambiguous queer history.

David O. Selznick, Letter to George Cukor, February 8, 1939.

David O. Selznick Papers 182.6Academy Award-winning director George Cukor lived relatively openly as a gay man in the "Golden Era" of Hollywood. As Vice Laws still dictated "morals policing," many queer people were criminally charged for a range of activities, including soliciting sex, attending pornographic theatres, or being caught in sexual acts with people of the same assigned gender. Though Hollywood studio executives, aware that stars viewed as immoral could subject the studio to boycotts from influential religious groups, used a range of coded language to explain why certain queer stars were single (such as portraying Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter as "workaholics"), the threat of public scandal through legal transgression loomed. While Cukor was at the height of his career, he was once the subject of a vice charge. However, studio executives, using their extensive power and influence in Los Angeles County had the charges dropped and expunged from his record, a not-uncommon practice when it came to protecting the reputations of profitable directors and stars at that time.

This letter, a precursor to him being fired from directing Gone With The Wind, is part of significant speculation about why Cukor was dismissed. While many argue his sexuality played no part in his firing, others (such as author Gore Vidal) have insisted otherwise.

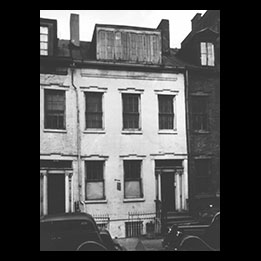

Unidentified photographer, Eve Adams's Tearoom, circa 1939.

New York City Municipal Archives REC 0040Eve Adams's Tearoom, also known as Eve's Hangout, was a lesbian club in Greenwich Village from 1925 until 1926. Owned and operated by Polish-Jewish writer Eva Kotchever and her partner Ruth Norlander, the club became a popular spot for lesbians in New York City and radical thinkers of the time, including fellow immigrant Emma Goldman. A space specifically designed to cater to women, the tearoom featured a sign stating "Men are admitted, but not welcome." After a June 1926 police raid, Kotchever was convicted of obscenity for being in possession of lesbian literature and was later deported back to Europe. She lived in Paris until she was arrested by the Nazis in 1943 and murdered at Auschwitz the same year.

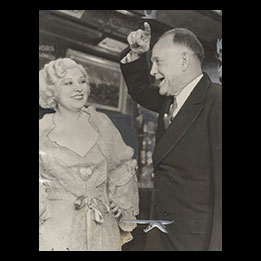

Unidentified photographer, Mae West and Billy Sunday. 1935.

New York Journal-American Photography Collection 2869Actress Mae West wrote several controversial plays, one of which was a 1927 script called The Drag that focused specifically on gay men. West, remembered as a gay icon, had many gay friends and advocated early for gay rights. She announced auditions specifically calling for gay men actors (who were forbidden by the actors' union to have speaking parts in plays). While critics were sour on the play, arguing that it capitalized on indecent subject matter, audiences flocked to its Connecticut premiere. In 1927, another of West's plays, Sex, landed her in jail for 10 days and saddled her with a $500 fine for indecency. Like The Drag, Sex spoke candidly about sexuality and both proved financially successful, despite editorial backlash against subject matter that was deemed unfit for public viewing. The incident gave West significant amounts of publicity, and she responded with characteristic wit that the time in jail and the fine had been well worth it.

Here is Mae West photographed with noted American evangelist Billy Sunday in 1935.

Unidentified photographer, The original Broadway cast of God of Vengeance by Scholem Asch, 1923.

Forward ArchivePolish-Jewish author Scholem Asch's play, The God of Vengeance (1906), infamously featured a lesbian kiss. After years of performances in Yiddish theatres in Europe and New York, the play premiered on Broadway in 1923 where, after a short run, the entire cast was arrested on obscenity charges. Like Hall's The Well of Loneliness, Asch's play received both ire and praise from a polarized public. Prominent Jews denounced the play, particularly for associations between Jewish immigrants and sex work, and the belief that the play would further expose assimilating Jewish immigrants in the US to antisemitism. Similarly, literary reviewers called into question the quality of the writing. Harry Weinberger, the play's producer and a lawyer, successfully overturned the obscenity convictions with the New York State Supreme Court on merit of "free speech." However, even usual advocates of free speech, such as the American Civil Liberties Union, offered only tangential support. This artifact represents the intricate complexities of not only questions of obscenity, but also the distinction between defending controversial literature based on freedom of speech versus the quality of the writing itself.

Here we see the original Broadway cast of The God of Vengeance.

Dorothy Bussy, Three letters to Mary Hutchinson, 1949–1950.

Mary Hutchinson Papers 9.9A classmate of Eleanor Roosevelt's at the London Allenswood Academy, the bisexual author Dorothy Bussy based much of her 1949 novel Olivia on her relationship with Marie Souvestre. Souvestre, the openly lesbian headmistress of the school, sought to cultivate independent minds for young women, and Roosevelt would keep a photograph of her beloved school principal on her desk for much of her adult life. In this letter, bisexual author Mary Hutchinson writes to Dorothy Bussy. Though Olivia was published years after The Well of Loneliness, the text found itself still enveloped in scandal and controversy upon its release by Hogarth Press (Leonard and Virginia Woolf's printing house).

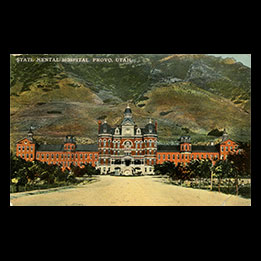

Souvenir Novelty Co., publisher, State Mental Hospital, Provo, Utah, picture postcard, circa 1903–1927.

Utah Historical Society Mss C 376Until the late 20th century, LGBTQIA+ identities were frequently classified as mental illnesses and disabilities, with some aspects of transgender identity still codified as such today. A 1919 mental hospital registrar from Utah showed a range of behaviors related to sex and sexuality that were cause for institutionalization. Medicine, particularly in the early 20th century, sought to strictly regulate gender. People could be institutionalized for being queer and subjected to inhumane treatments as part of involuntary commitment. The lobotomy became synonymous with gender regulation in American mental health practices until fears of the Cold War and the possibility of "mind control" shifted American public opinions about this practice. However, mental hospitals, doctor's offices, and psychiatrists were frequent and brutal sites of LGBTQIA+ regulation and punishment, a theme that appears regularly in film and literature.

Censorship and Blacklisting

A plethora of shifting social conventions only aggravated questions of censorship and the consequences of publishing "banned books." Contrary to a belief in a linear view of societal progress where increasing social liberalism decreases the impact of censorship as time moves forward, the texts below show that Victorian morality and religious political influence in the world of media production did not cease or even loosen their grips at the end of the 19th century. Global political events, such as the rise of communism, the collapse of European political dominance through global empires, and the catastrophic impacts of two world wars merely shifted the methods in which social conventions dictated what could and could not appear in public.

While the Comstock Laws and European obscenity laws eventually were struck down, new forms of censorship took their place. In the United States, fears of communism conflated with old stereotypes about gender and sexuality. The Motion Picture Production Code (1934–1968) severely restricted what sorts of sexual and political messages could appear in American film. Americans, for their part, began to conflate the more public expressions of same-gender attraction and pushes for gender equality with communism and sympathy with the Soviet Union. Believing that queer people were more likely to be successfully blackmailed by foreign agents, queerness became a "coded trait" for communist sympathy. Queer characters appearing in film were typically viewed as duplicitous, acting one way towards protagonists while secretly harboring hidden agendas that focused on obtaining power. Hall and Troubridge both were politically antagonistic towards leftist causes (a point of contention between the pair and other popular British writers of the time who tended to be more sympathetic to socialist movements). The two held deeply conservative views during the interwar period, and Evgenia Souline had been an anti-communist before leaving Russia after the Communist Revolution. While Hall died before the height of the Cold War, other queer authors found their own work politically challenged and censored, with some later finding themselves blacklisted and unable to work in the 1940s–1960s.

The texts below touch on the political ramifications for authors whose content found itself mixed up in the political consequences of censorship in the Cold War period. Instructors using these documents might ask students to think critically about how politics and sexuality become conflated in historical memory. To what degree are queer texts political and to what degree are politics superimposed on queer authors and their work?

Lillian Hellman, The Children's Hour, cover (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1934).

Academic Center Library Books AC-L h 368 chi 1934Hellman emerged as one of the most gifted play and screenwriters of the mid-twentieth century. Outspokenly leftist in her views, Hellman found herself blacklisted in the 1950s at the height of Cold War paranoia and the threatening presence of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Citing the Fifth Amendment, Hellman refused to cooperate with HUAC questioning, which severely impacted her ability to work in Hollywood for some time.

Her 1934 play, The Children's Hour, focuses on the two principals of an all-girls school whose lives are thrown into chaos after a vindictive student begins a rumor that they're having a lesbian affair. By 1961 when the film became a major motion picture, the hints of Cold War politics are evident, with mere gossip and hearsay proving powerful enough to completely destroy the lives and reputations of others.

Motion Picture Association of America, Letter to Jack L. Warner, October 5, 1965.

Ernest Lehman Collection 117.10Openly gay playwright Edward Albee's most famous play, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, faced threats when first staged in 1962 of a canceled production over what censorship laws deemed "indecent." The play, which features explicit language, frank conversations about sexuality, and veiled allusions to abortion, faced significant edits prior to being made into the 1966 motion picture. While the play did not feature direct queer content, Albee had produced other plays with unambiguously sexual content, including the 1958 The Zoo Story.

Unidentified photographer, A Streetcar Named Desire, film still, 1951.

Harry Ransom Center 58/335Like Albee, the openly gay playwright Tennessee Williams saw his work undergo significant revisions under the Production Code when his play, A Streetcar Named Desire, was adapted to film in 1951. The play, which featured unambiguous queer content, underwent edits that changed Blanche's dead husband from a closeted gay man to an ambiguously "weak" one. Furthermore, the film's director, Elia Kazan, gave evidence to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. Himself a former member of the New York Communist Party, Kazan infamously gave names to HUAC, which, in turn severely damaged the careers of suspected Hollywood communists. Among those whose career was severely damaged was Kim Hunter, who starred as Stella in both the Broadway and film productions of A Streetcar Named Desire.

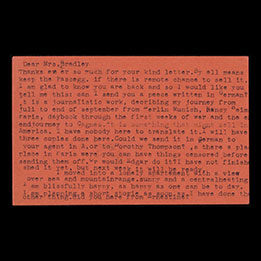

Christa Winsloe and Cecile Antoine, correspondence to Jenny Bradley from or about Christa Winsloe, 1939–1945.

William A. Bradley Literary Agency Records 66.1A 1931 German film adaptation of Winsloe's play of the same name, Women in Uniform, was notable for featuring unambiguous lesbian content in Weimar Germany. This time period in German history became synonymous with greater experimentation with film and with queer themes becoming increasingly visible in a more tolerant inter-war Berlin-based culture. The film, as with other films of the time period that engaged in experimental stylistic choices and took up themes around gender and sexuality, was eventually banned by the Nazis later in the 1930s and labeled "Degenerate art."

Free Speech and Artistic Merit

Charges of obscenity became gradually less significant as authors and artists began to challenge laws governing human sexuality. For authors, the question of literary merit and artistry became a central focus point in the battle against censorship. Hall was particularly bruised that her notable defenders (such as the Woolfs) during her original obscenity trial defended The Well of Loneliness on the basis of free speech, not on the basis of artistic integrity. While it is undoubtedly still regarded as an influential and watershed text in queer literature, critics of the book were and remain divided on the question of whether it is a good book.

Questions of literary merit and artistic genius are arguably subjective. However, for the purposes of legally defending texts and fighting censorship, the critical assessment of a writer's talents became a valuable tool when it came to persuading legal courts and the courts of public opinion. This section examines the delicate questions of book censorship and artistic quality. While some argue that all books should be published without legal barriers due to liberal-humanist values regarding the freedom of speech, Hall did not want her work simply defended based on a "right" to publish. This subcategory specifically examines the role of critical evaluation and authorial talent in histories of the defense and assessment of queer literature. At what point in the modern era did people begin to culturally value explicitly queer content in books, art, and media? When did queer authors who wrote about queer themes achieve critical acclaim? What is the value of examining the quality of queer art rather than offering blanket defenses that all literature should be publishable?

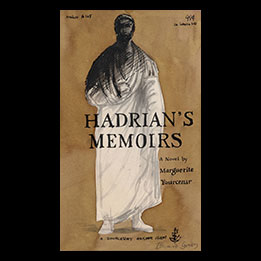

Edward Gorey, cover design for Hadrian's Memoirs by Marguerite Yourcenar, undated.

Edward Gorey Art Collection 73.359.2Queer artist Edward Gorey illustrates the 1957 translation into English of Marguerite Yourcenar's Mémoires d'Hadrien. Living most of her adult life with her partner Grace Frick, Yourcenar proved to be a prolifically gifted writer. Winning many awards (including the prestigious Erasmus Prize), Yourcenar is remembered today both for her critically-lauded collection of writings, and her role as the first woman elected to the French Academy, the body of officials who govern all matters related to the French language.

Along with Colette and Marcel Proust, Yourcenar is remembered as one of France's most influential queer authors.

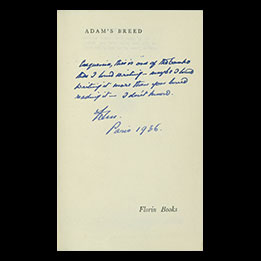

Radclyffe Hall, Adam's Breed (London: Jonathan Cape, 1933), inscribed and signed by Hall, 1936.

Book Collection PR 6015 A33 A64 1936Hall signs this copy of Adam's Breed using the intimate name "John." Adam's Breed (1926), about the psychological impact of the First World War on those who survived it, became a critically-acclaimed and award-winning bestseller. It was the success of this text and the general agreement that the text was a well-written piece of fiction that gave Hall the motivation to pursue writing The Well of Loneliness. The text also exposes some of the literary questions surrounding form and content that proved challenging for authors of her time. The impact of World War One on literature was profound, shifting style and subject matter away from upper-class Victorian plots, characters, and plot structures towards more experimental and daring texts.

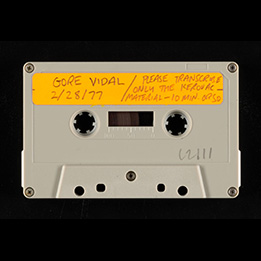

Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee, interviewers, Interview with Gore Vidal, sound recording, February 28, 1977.

Sound Recordings Collection C 2111Openly bisexual, the intellectual and social comentator Gore Vidal is recorded here with Barry Gifford and Lawrence Lee discussing the queer histories of the Beatnik poets.

Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers, Speaking at The Poetry Center, YMHA, New York, sound recording, May 8, 1954.

Sound Recordings Collection R 0160.1Here Carson McCullers and Tennessee Williams discuss literature and writing in an interview. Both queer and both Southern, the two authors achieved significant critical acclaim for their work and are today regarded as two of the most influential American writers of the twentieth century.

Robert P. Mills, Two letters regarding a theatrical adaptation of Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin, May 1962.

Robert Park Mills Papers 3.2Here, Baldwin bristles over suggestions that he remove queer themes and other culturally "sensitive" topics from a theatrical adaptation of his 1956 novel Giovanni's Room. While the letter does present Baldwin as uncompromising in his defense of his artistic vision, doing so came with serious potential consequences for his career and livelihood. While now regarded as one of the most significant Black authors in American history, his reputation with even more socially liberal literary and theatre audiences was not as insulated as one might think. In addition to potential homophobia, racism doubtlessly compounded Baldwin's efforts to take the same kinds of risks that White, queer authors might be afforded.

Alice Walker, Five Poems (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1972).

Smithsonian InstitutionAlice Walker became the first Black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for her 1982 novel, The Color Purple. Centered on relationships between Black women (including romantic and sexual ones), the text is held up as a watershed book in queer-of-color literature. However, the book was released to much controversy from social conservatives in Reagan-era America who objected to it on the grounds of same-sex content.

Now considered a staple of American literature, the book continues to be targeted for removal from classrooms and libraries on similar arguments against what challengers argue is sexually explicit content.

Here are five short poems published in 1972 in purple ink. Like The Color Purple, these poems center the experiences of queer Black women in a homophobic, racist, and sexist culture. However, unlike Hall who appeals for sympathy for queer characters, Walker emphasizes survival, strength, and revolutionary potential in her narratives.

Edward Williamson, "Willa Cather's Latest Book Is Another Triumph," September 23, 1923.

University of Nebraska-Lincoln LibrariesHere we see a 1923 review for Willa Cather's A Lost Lady. Regarded as one of the finest authors of her generation, Cather is at least partially credited with moving the intellectual setting of American literature from New England to West of the Mississippi River. She is regarded in the present as one of the first "great" women authors in American history, although she herself bristled at categorizations of "women's writing." In addition to her writing, she was an essayist and critic of new forms of writing, expressing both admiration and disdain for many popular authors of her time. Later, male authors who took up the midwest as a setting critiqued her work as old fashioned and apolitical. However, her books have enduring legacy for their sense of artistry and strong narrative descriptions of setting and characterization.

Ulysses in America

James Joyce benefited enormously from a tireless circle of lesbian allies with significant influence in the publishing world.

In her graphic memoir, Fun Home, lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel uses Joyce's Ulysses as a rhetorical device throughout the book. She positions the text, along with Hall's The Well of Loneliness, as both emotionally and erotically significant to her adolescent "coming out" process. At the book's conclusion, she notes that Sylvia Beach, her partner Adrienne Monnier, and Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap (who were prosecuted for publishing excerpts of the book in The Little Review) were all lesbian women. "Perhaps it's just a coincidence," Bechdel writes, "that these women… were all lesbians, but I like to think they went to the mat for this book because they were lesbians, because they knew a thing or two about erotic truth," (229). However, for Radclyffe Hall, Joyce and his magnum opus hovered in close proximity to her own struggles to publish The Well of Loneliness in both the United Kingdom and the United States. While Joyce was heterosexual, his work's publication frequently highlighted gender and sexuality politics in Europe and North America, and a range of political leftists, feminists, and queer people came to its defense. For example, the communist feminist Harriet Shaw Weaver acted as a benefactor for Joyce.

Anxieties about changing understandings of gender and sex hovered over Ulysses's American obscenity trial in 1921, in eerie similarity to the late 1920s trials of The Well of Loneliness. As with the proposed witnesses for Hall's trials, Heap and Anderson did not speak at the Ulysses trial so as not to further transgress gender norms. Unlike The Well of Loneliness, however, Ulysses was deemed obscene in court, and The Little Review was forced to cease serial publication.

As Bechdel and other queer-feminist authors have noted, Joyce had no qualms relying on the unpaid work of queer women when it came to putting their own professional lives on the line to publish and defend his work. For Hall, the ghosts of Ulysses and its subsequent obscenity trials on both sides of the Atlantic guided how she and her defenders approached defining The Well of Loneliness.

However, while authors such as Hall, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, and Colette dominate discourse on queer writing in the early modern period, this section hopes to center the invaluable and often unrewarded contributions of queer women publishers during this time period, particularly when it came to bearing the load of legal challenges and navigating obscenity laws.

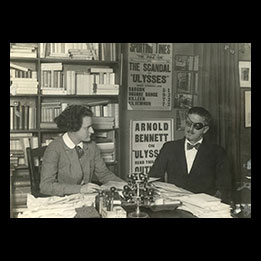

Unidentified photographer, James Joyce with Sylvia Beach in her bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, in Paris, 1922.

James Joyce Literary File Photography Collection 957:0032:0040James Joyce's experiences publishing Ulysses would provide significant footwork for Radclyffe Hall during the author's own brushes with obscenity and publishing in American markets. While earlier collections note the significant contributions Beach made to publishing Ulysses at great personal expense, this photograph of Sylvia Beach and Joyce also brings into question the merit of a text.

Ulysses, with a section of the text featuring metaphorical masturbation, was banned from distribution in the US in 1921 under the Comstock Laws.

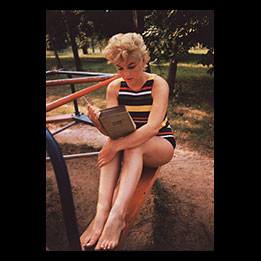

Eve Arnold, photographer, Marilyn Monroe reading Ulysses, undated.

Eve Arnold Photography Collection 999:0031:0010Actress Marilyn Monroe is photographed here by Eve Arnold reading Ulysses in 1954. Monroe has long been regarded as a "gay icon," and recent biographical scholarship suggests Monroe was queer and had meaningful romantic and sexual relationships with women.

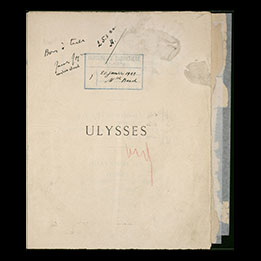

James Joyce, Ulysses, cover of final corrected page proofs signed by Sylvia Beach and James Joyce, 1922.

James Joyce Collection MS-02232In addition to her publication of Ulysses, Beach's Paris bookstore, "Shakespeare and Co.," served as a vital location for literary history, populated with some of the most famous authors of the day, such as Ernest Hemingway, T. S. Eliot, Janet Flanner, and F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

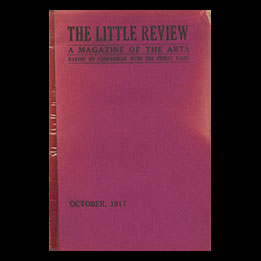

Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, The Little Review (Chicago: M.C. Anderson, October 1917).

Book Collection AP 2 L647In America, lesbian publishers Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap undertook the task of printing excerpts from Ulysses, starting in 1920. The Little Review became a proverbial "who's who" to some of the greatest authors of the early 20th century, including several openly queer writers who wrote unambiguously about same-sex attraction. Ezra Pound began mailing the pair excerpts from Ulysses, which they published until the Post Office burned issues of their magazine containing the text and tried the pair for obscenity. While technically focused on Joyce, the trial also exposed greater cultural anxieties about other works of literature the magazine had published, including poems and love stories by queer authors.

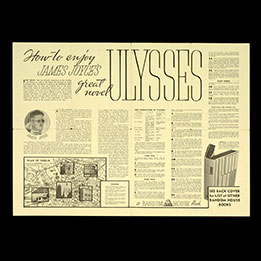

Random House, "How to enjoy James Joyce's great novel Ulysses," advertisement, 1934.

James Joyce Vertical File Collection FF-1Here we see a 1934 Random House advertisement for "How to Enjoy Ulysses." This artifact shows the rapid evolution of the text from a challenged book to its integration in English-language literature as an experimental work of great importance.

Takedown Notice: This material is made available for education and research purposes. The Harry Ransom Center does not own the rights for these items; it cannot grant or deny permission to use this material. Copyright law protects unpublished as well as published materials. Rights holders for these materials may be listed in the WATCH file. It is your responsibility to determine the rights status and secure whatever permission may be needed for the use of any item. Due to the nature of archival collections, rights information may be incomplete or out of date. We welcome updates or corrections. Upon request, we'll remove material from public view while we address a rights issue. The unpublished works, correspondence, diaries, and daybooks of Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge are under copyright in the United States. The Ransom Center is grateful to Alessandro Rossi Lemeni Makedon, the representative of Troubridge's estate, who has granted permission for the Center to share the papers of Troubridge.